Great expectations: The reality of local health care

As Los Alamos organizations try to make a difference in local health care, they must decide which problems they can control

Photographs by Minesh Bacrania

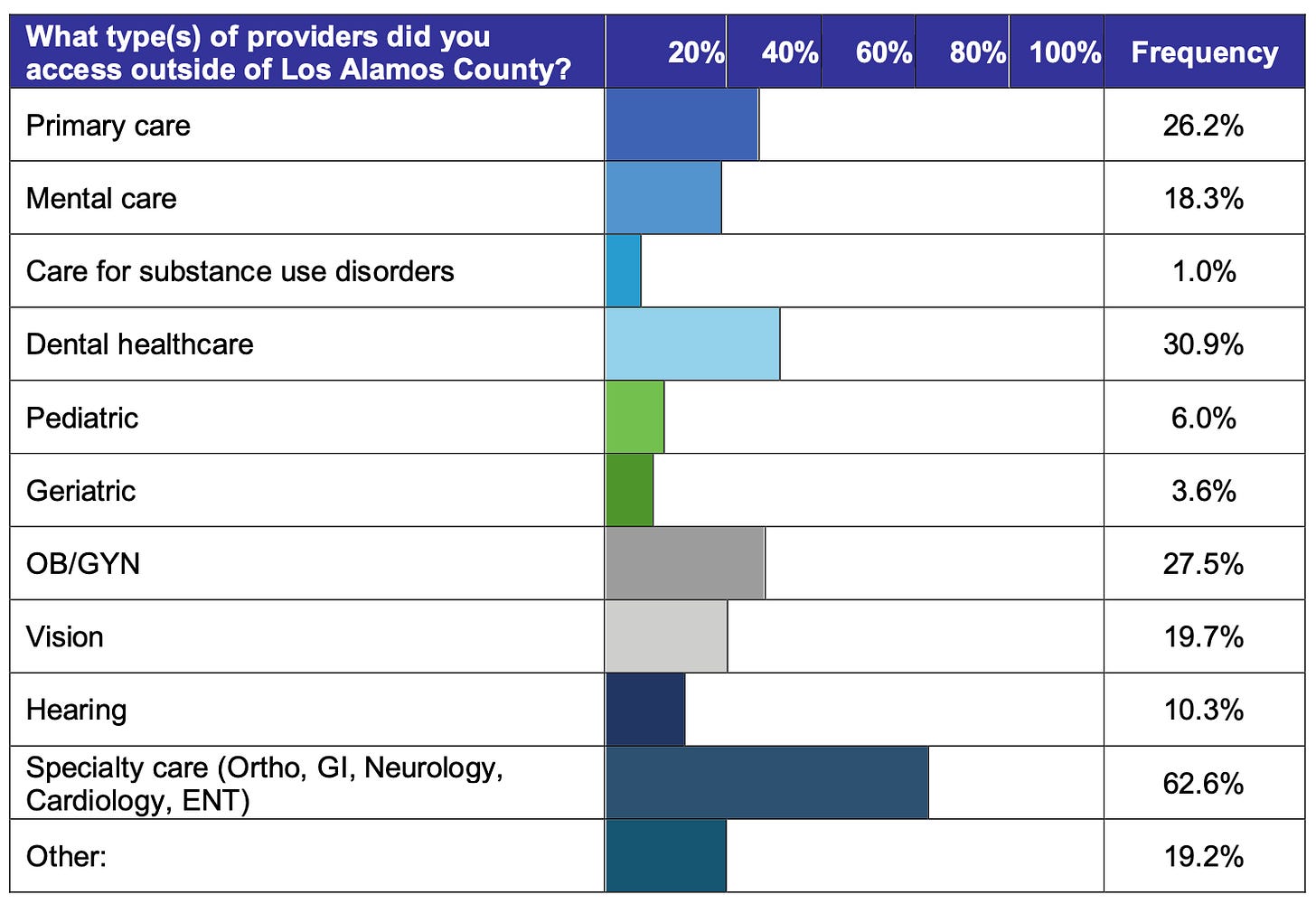

In 2024, Los Alamos was named the second-healthiest county in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. The same year, the Los Alamos Medical Center was voted one of New Mexico’s best hospitals by Newsweek. These designations came as the Los Alamos County Health Council conducted a survey about local health care, asking Los Alamos County residents about their experiences with both mental and physical care, as part of the development of the County’s Comprehensive Health Plan. While 63% of the 1,034 respondents said they were satisfied with the health care they’d received in Los Alamos, only 50% felt that care was easily accessible and about 66% of survey respondents reported seeking health care off the Hill due to local provider shortages and the quality of available options, particularly for specialized care.

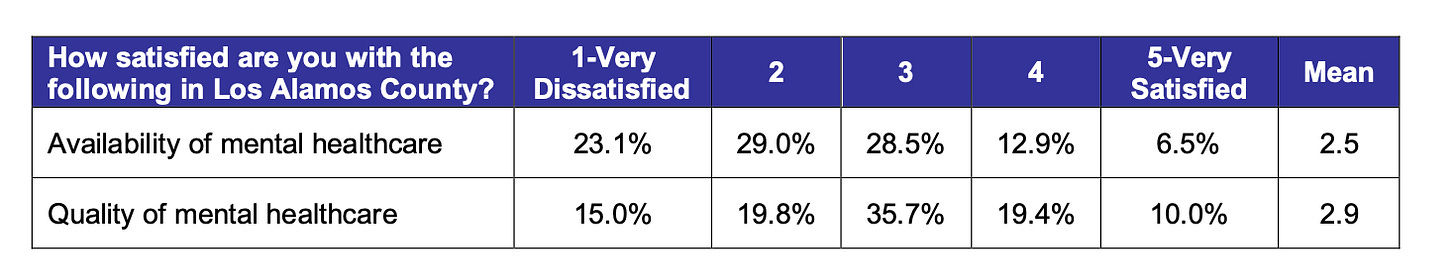

Especially troubling was that 35% of the survey’s respondents delayed or avoided seeking general medical care, and 27% delayed seeking mental health care due to difficulties finding affordable providers in a timely manner. Substance use disorder care also received poor marks, with nearly half of the respondents reporting that they were dissatisfied with both access to and the quality of the care available in Los Alamos.

The county’s survey provided a glimpse into what Los Alamos residents expected their local health care system to deliver, but in an effort to understand the health care landscape in our community, Boomtown looked into the various attempts to address these external factors — health care worker shortages, insurance troubles, and provider availability — being made by the county, the lab, the local hospital, and other providers. While incremental gains have been made, we also found that many factors remain beyond the control of these organizations.

The local health care landscape

For doctors in Los Alamos, the business of health care has changed drastically over time. One physician, who spoke to Boomtown on the condition of anonymity, said that when she began working in Los Alamos in the 1980s, most doctors had their own individual practices. This meant that, while physicians might have worked out of the same physical facility, they were each responsible for running their own businesses. Today, most local private practices have several doctors and lower-level providers working for them.

On the positive side, she noted that physicians now have to work fewer hours and have to be on call less often, and they are able to share equipment and technology with other members of the practice. However, over time, the growing amount of documentation required for patient care, as well as lower reimbursements from medical insurance companies, have forced practices to hire additional staff to deal with issues like billing, insurance, and physician credentialing.

The majority of health care providers in Los Alamos are concentrated in one massive building located at Diamond Drive and Trinity Drive. The large complex is home to Los Alamos Medical Center, Medical Associates of Northern New Mexico, Los Alamos Medical Care Clinic, and several smaller private practices that each have their own doctors, support staff, business systems, and unique insurance-billing protocols.

LAMC and local services

Los Alamos Medical Center is the single acute-care hospital in Los Alamos County, and while much of the staff is employed directly by LAMC, the hospital is also staffed through contracted agencies like CompHealth and Emergent Medical Associates, which help recruit and hire doctors, often on a temporary basis. This system of contracted physicians and separate organizations is typically why people receive multiple bills from LAMC after each visit, and why patients often have to pay facility fees in addition to individual professional fees.

The helipad behind LAMC serves as the regional base for two air ambulance helicopters operated by Classic Air Medical, which is owned by Utah-based Intermountain Health. Despite its proximity to LAMC, most helicopter flights to and from the helipad are not transporting LAMC patients but instead are responding to calls for service around Northern New Mexico.

Emergency medical services in Los Alamos County and at Los Alamos National Laboratory are provided solely by the Los Alamos Fire Department under a $500 million, ten-year cooperative agreement between Los Alamos County and the National Nuclear Security Administration.

Tracie Stratton, CEO of LAMC for the past four years, said the hospital’s offers to potential doctors are “not out of line” with similar-sized facilities and that other things beyond her control have hindered recruitment efforts.

“There are a lot of things that are out of my control that impact my ability to recruit,” she said. “I can’t control medical malpractice. I can’t control what the legislature does. I can't control the cost of living up here. I can’t control the housing.”

Mental health care

Results of the county’s health survey showed that Los Alamos also has a high demand for mental health care services, with more than 50% of respondents indicating they’ve felt dissatisfied with the availability of mental health care in town. Additionally, about 27% said they’d sought mental health care off the Hill, particularly when it comes to pediatric mental health. (LAMC primarily focuses on outpatient care, which does not include mental health.)

One possible solution to the lack of mental health care in the area is to hire telehealth doctors. This would allow doctors from other parts of the state, or even country, to see patients, as long as they’re licensed in New Mexico. However, many people may prefer to see a provider in person, so expanded telehealth services likely wouldn’t appeal to every person seeking mental health care.

Health care as a business

Local physician availability, housing costs, and a lack of up-to-date technology are contributing factors to the local health care problems outlined by the survey results, but these are not the only reasons that many in the community reported feeling underserved. Troubles with insurance and other issues with for-profit health care companies often have significant consequences for the county, as well as the state and nation as a whole.

Boomtown has previously reported on the challenges of recruiting medical providers to New Mexico, and specifically Los Alamos.

READ MORE: ‘A tremendous gap’: Local doctors on the challenges they face in Los Alamos

LAMC is owned by Lifepoint Health, a for-profit health care company that manages hospitals around the country. Lifepoint was acquired in 2018 by Apollo Global Management, a private equity company that owns 220 hospitals around the country, making it the largest company of its kind in the nation.

Private equity acquisition has become an increasingly popular trend in U.S. health care, and by one 2024 estimate, 30% of all for-profit hospitals in the country are now owned by a private equity company. New Mexico is considered one of the most at-risk states for hospital acquisitions by these types of companies.

Lifepoint and Apollo Global Management received recent scrutiny from the U.S. Senate over hospital staffing conditions, billing issues, and bankruptcies.

“While these issues are not limited to private equity, they are exacerbated by the private equity business model, which hinges on highly leveraged debt, little equity, and the need to obtain outsized returns within a limited time,” Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI), the chairman of the Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, wrote in a letter to Apollo Global Management and Lifepoint.

Furthermore, a report published by the Senate Budget Committee found that hospitals owned by Apollo Global Management were often understaffed and were sometimes shut down, especially concerning considering that Lifepoint mostly manages hospitals in rural and underserved areas.

“The findings of the investigation call into question the compatibility of private equity’s profit-driven model with the essential role hospitals play in public health,” the report concluded. “The consequences of this ownership model — reduced services, compromised patient care, and even complete hospital closures — potentially pose a threat to the nation’s health care infrastructure, particularly in underserved and rural areas.”

Many local health care providers in Los Alamos feel that issues with staffing shortages, facility conditions, and outdated equipment at LAMC can be attributed to private equity’s mission of prioritizing profits over patients. For example, the hospital had to wait years to get a 3D mammogram machine, and due to changes in the way isotopes are transported, Lifepoint got rid of LAMC’s nuclear medicine department and Los Alamos no longer conducts nuclear stress tests.

“Tracie Stratton does a great job,” said a local physician who spoke to Boomtown on the condition of anonymity. “I just don’t think Lifepoint has Los Alamos’ best interests at heart.”

Local insurance

Despite Los Alamos’ reputation as a wealthy, one-company town with 99% health-insurance coverage, another health care access concern patients have noted is that their insurance may not be accepted everywhere.

For example, in 2023, Smith’s Food and Drug — the largest pharmacy in Los Alamos — stopped accepting claims for prescriptions through the insurance company used by the largest employer in the region, resulting in Nambe Drugs becoming the only local pharmacy option.

Carina Condado, a former Smith’s pharmacist who now works in Santa Fe, said this was the result of a national dispute between Express Scripts—a pharmacy benefit manager contracted by LANL’s insurance provider Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Mexico—and The Kroger Company, the parent company of Smith’s.

Pharmacy benefit managers are third-party groups contracted by both public and private insurance companies to act as middlemen between prescription drug manufacturers, insurance companies, and pharmacies. PBMs create formularies — or lists of prescription drugs which are covered by different insurance plans — and negotiate discounts, called rebates within the industry, from drug manufacturers for themselves or for insurance companies.

PBMs, which are paid by both drug manufacturers and insurance companies, thus control both sides of the transaction: how much insurers and patients pay for medications, as well as how much money pharmacies receive for distributing these drugs. As of 2022, just three PBM companies processed nearly 80% of all prescription drugs in the country — Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and Optum Rx.

In some cases, PBMs drive up the cost of prescription medications because they keep a portion of the rebates they negotiate instead of paying the full amount to insurance companies or patients. They may also institute what’s known as “spread pricing,” in which insurance plans are charged more for a drug than pharmacies are reimbursed for selling it, allowing PBMs to keep the difference.

Condado said that spread pricing is what caused the dispute between Express Scripts and Kroger. Earlier this year, Kroger and Express Scripts renewed their relationship to an extent, but Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Mexico insurance holders were not part of that agreement.

These insurance issues are not a new problem though. Los Alamos residents have had other challenges with local hospitals and insurance companies since the 1990s when LANL entered an insurance contract with Lovelace Health System.

For people with insurance through LANL, health care would only be covered if they sought care at Lovelace’s clinics in Albuquerque. Private practice doctors in town lost business, giving Lovelace the opportunity to buy up their smaller local practices. A few years later, when Lovelace and LANL didn’t renew the contract, doctors who had gone to Lovelace suddenly had nowhere to go.

Some of those doctors bought back their practices, but Tyler Taylor, a retired physician from Los Alamos, said he felt tension between those physicians and the ones who had not had to do so.

“I just had never lived in that kind of situation before,” Taylor said. “So that was also a real part of why the doctors didn’t cooperate near as much as I had been used to.”

What comes next?

Tracie Stratton described LAMC as “the cornerstone for health care in the community,” but emphasized that as a rural hospital, LAMC cannot and will not be all things for all people.

Stratton used the example of an open-heart surgeon, a position that would not only be difficult to recruit but would require the hospital to hire staff in other specialties as well. Additionally, for these physicians to stay, they would require a steady flow of work, which Los Alamos could likely not provide.

“I’m not going to put you, as a community member, at risk by bringing in a specialist that cannot maintain their competencies,” she said.

Still, most of the physician roles lacking in the county are primary care providers and more general specialty doctors. LAMC and other private practices continue to recruit for positions in high demand, including family practice, gastroenterology, and cardiology. However, the reality is that, despite Los Alamos’ influence and affluence, the county’s specialist medical care options are unlikely to expand.

“We’ll continue to evaluate, we’ll continue to assess, we’ll continue to identify what are the needs, what service lines make sense for an acute care hospital,” Stratton said. “We’ll continue to adjust and adapt as needed to meet the community needs.”

There are other communitywide health initiatives that the county and other organizations are trying to implement as well, and the 2024 Comprehensive Health Plan outlined many ways in which they could help close the gaps in local health care, including for behavioral and mental health.

Jessica Strong, the director of the county’s Social Services Division, said the county is also considering how it can best work with surrounding communities and governments, and has had conversations with Stratton and LAMC about working together on future health care initiatives.

Stratton said that it’s a “topic of conversation” that she’s had with the county but declined to comment on any specific initiatives.

Another pressing issue is the availability of medical transportation, both emergency and non-emergency. Stratton said that having to send people to other hospitals and finding a place for them to receive advanced care during an emergency is part of LAMC’s job.

However, one nurse at the hospital suggested that Los Alamos, as a community, should look for ways to improve transportation and come up with a robust system, outside of ambulances and helicopters, which could help residents get to regional care centers and other hospitals and bring them back. (Currently, the Los Alamos Retired and Senior Organization is the only group in town that currently has a transportation program like this.)

As a top employer and economic force in Northern New Mexico, LANL has also gotten more involved in health care through its Community Partnerships Office. Frances Chadwick, the staff director at LANL, said that since two-thirds of the lab’s current workforce resides outside of Los Alamos, helping the seven counties surrounding Los Alamos is a priority as well.

The U.S. Congress oversees how LANL’s funds are allocated, but while the lab cannot directly address community housing or recruiting issues, it has people dedicated to helping in the community both monetarily and through behind-the-scenes relationships. For example, J. Patrick Fitch, LANL’s deputy director for science, technology, and engineering, is on the LAMC advisory board. Triad, the private corporation contracted by the DOE to manage LANL, also donated toward the new Christus St. Vincent Regional Cancer Care Center, which opened in July in Santa Fe.

Meanwhile, Christus St. Vincent, which is owned by Christus Health, a Catholic nonprofit hospital conglomerate based in Texas, has been building a presence in Los Alamos by purchasing property for a prime downtown location. The purchase was completed in March with the goal of building a 25,000 square-foot “multi-specialty clinic.” However, a Christus spokesperson told Boomtown in August that it was too early to tell how the new Los Alamos facility will serve the town, and that it will likely not be open for a few years.

Still, new options are needed, and they are welcomed by many in the community.

“When you have a single health care system monopoly, it really allows for complete complacency, and people don’t have an option and they feel cornered,” said Susie Belle Peterson, clinical manager at Los Alamos Visiting Nurse Service. “I really think that it’s going to help give people options, and ultimately, it’s going to drive patient satisfaction to truly be the center again.”