Road diets: reimagining the major thoroughfares in Los Alamos

When the County proposed reducing westbound lanes on NM 4 in White Rock, many residents referred to it a “road diet.” County staff were quick to clarify — it’s not technically a road diet. Los Alamos already put a section of Trinity Drive on an actual road diet, which was completed in 2019, and another section of the same road is slated for a “hybrid” road diet in 2026. While a proposed lane reduction on NM 4 in White Rock isn’t technically a road diet, these projects share a common goal: making streets safer for everyone.

So what is a road diet? And why are communities across the country increasingly choosing this particular tool for street safety?

What is a road diet?

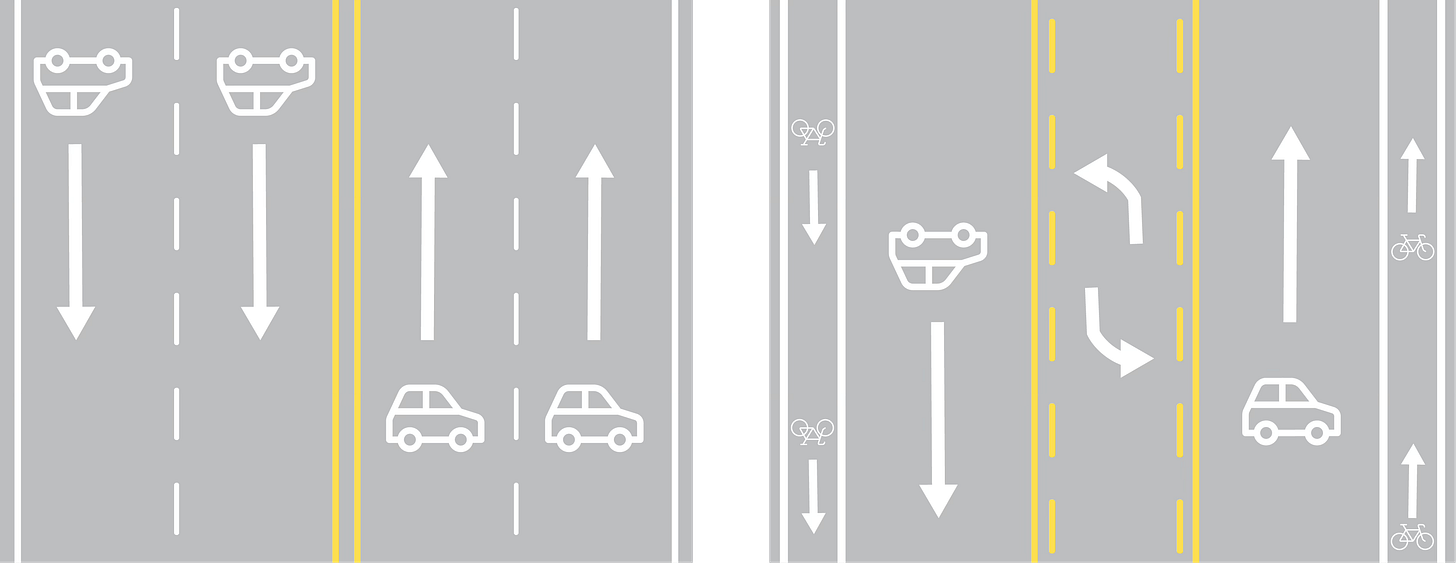

Road diets are a safety measure — one of several strategies for “traffic calming.” Sometimes the “weight loss” involves making lanes skinnier, but road diets usually convert a four-lane road with two lanes each way into a three-lane road. The extra space is then reallocated to bike lanes, wider sidewalks, or turn lanes. This strategy aligns with the Safe Systems Approach, which recognizes that humans make mistakes and aims to design roads that minimize the consequences of those mistakes.

While it might seem counterintuitive that removing lanes could improve traffic flow, research shows that road diets can make streets work better for everyone. The center turn lane allows left-turning vehicles to wait without blocking through traffic, while the reduced number of lanes means fewer collision points where accidents are most likely to occur. Studies have shown road diets reduce crashes by an average of 29% while maintaining traffic flow, because most delays on four-lane roads are caused by cars stopping in travel lanes to make left turns.

Road diet on Trinity Drive

According to the Federal Highway Administration, road diets work best on streets that carry fewer than 20,000 vehicles per day — roughly what you might expect on the main street of a small to medium downtown. In Los Alamos, the vehicles-per-day for Trinity Drive averages about 14,000 to 17,000.

Los Alamos County is advancing safety improvements on Trinity Drive through a series of road diets. The initiative began with a 2016 road safety audit, according to a Public Works presentation at the Aug. 6, 2024 County Council meeting. Based on the analysis of existing safety issues, NMDOT recommended a variety of countermeasures, leading to the initial project.

Phase one, completed in 2019, emerged from discussions about The Hills apartment complex on Trinity Drive. When NMDOT planned to resurface Trinity in 2019, they agreed to implement a conventional road diet from 39th Street to Oppenheimer Drive. “Even though there’s a lot of people that feel the road diet makes traffic worse, we’ve shown through travel time studies that it doesn’t,” explained Deputy County Manager Juan Rael in an interview with Boomtown.

According to Rael, even during the challenging period when Canyon Road was closed and traffic was redirected to Trinity, traffic kept moving. “The road diet segment continued to flow with only a minor reduction in speed,” Rael said. “The primary constraint affecting capacity [i.e., the bottleneck] is the signalized intersection at Diamond and Oppenheimer.”

The first phase of the Trinity road diet showed significant safety improvements without major traffic impacts. In an interview with Boomtown, longtime County Engineer and current Public Works Director Eric Martinez said, “After doing the analysis, lo and behold, it actually worked — it reduced conflicts, and it had that safety aspect.” He also pointed out that adding bike lanes aligned with the County’s Bicycle Master Plan.

Building on phase one’s success, in September 2024, Los Alamos County Council approved phase two — a “hybrid” road diet for Trinity Drive between Oppenheimer Drive and Knecht Street. The project, funded by a $4.25 million grant from the NMDOT, aims to enhance safety for all road users while maintaining traffic flow.

Phase two, expected to begin construction in 2026, is a “hybrid.” Unlike a conventional road diet, which adds a center turn lane between one lane each way, the approved plan will replace one westbound traffic lane with a two-way turn lane while maintaining two eastbound lanes from Oppenheimer Drive to Knecht Street. Like a conventional road diet, repurposing one lane of traffic allows for dedicated bike lanes in both directions and improved pedestrian infrastructure.

In an interview with Boomtown, Los Alamos County Project Manager Justin Wilson described the hybrid as “a type of priority system.” “Historically, older roads were designed primarily for vehicles,” he said. “While vehicles will still probably be the dominant users, the goal is to provide better access for bicycles and pedestrians.”

Lessons from other communities

Road diets aren’t unique to Los Alamos. Communities across the country, fed up with crashes, traffic snarls, and depressed economic activity, have been turning to road diets as a solution.

In Lancaster, CA, a nine-block road diet transformation became a regional draw and sparked economic development since its completion in 2010. According to city data:

57 new businesses opened in downtown Lancaster

Retail sales rose 57%

More than 800 housing units were built or refurbished

Commercial occupancy reached 96%

Nearly 2,000 jobs were created

Total economic impact was estimated at $282 million

In Orlando, FL, a 1.5-mile road diet on Edgewater Drive yielded similar results:

34% fewer crashes and 68% fewer injuries

Property values increased 8-10% in residential areas and 1-2% for commercial areas

Travel times improved by 25 seconds despite increased traffic volume

Walking and bicycling rates rose by 56% and 48%, respectively

In Reston, VA, an analysis of road diets on Lawyers Road and Soapstone Drive showed:

Overall crashes decreased by 70% on both roads

Travel times remained stable, addressing initial congestion concerns

47% of surveyed respondents reported increased bicycle use on Lawyers Road

69% felt the road was safer post-diet

Improved connectivity to local parks and trails boosted cyclist and pedestrian network use

In Seattle, WA, a road diet on Stone Way North also demonstrated success. After implementation:

Overall crashes decreased by 14%

Injury crashes dropped by 33%

Angle crashes decreased by 56%

Bicycle volume increased 35%

Pedestrian collisions decreased 80%

Part of a bigger picture

With a Pedestrian Master Plan under review and efforts to align the Bicycle Master Plan, Downtown Master Plan, and ongoing projects like the Urban Trail, some of our streets — especially Trinity Drive — are changing. At the Sept. 10, 2024 Council meeting, Rael explained that phase two of the Trinity road diet fits into a bigger picture. “We’re following a ‘safe streets for all’ concept that Council passed many Councils ago,” he said. “We look at roadway projects from a Complete Streets standpoint.”

Los Alamos isn’t alone in reimagining its streets to work better for everyone. While change isn’t always comfortable — especially at first — the data from other communities show that taking a chance on safety-focused design pays off in the long run. These projects are intended to create streets that aren’t just safer, but more welcoming and accessible for the whole community.

Road Diet Myths and Facts

Myth 1: “Road diets divert traffic onto other streets”

Reality: Studies show that on roads used by fewer than 20,000 vehicles per day, road diets have minimal or even positive impact on vehicle capacity. Left-turning vehicles, delivery trucks, police enforcement and stranded vehicles can move into a center lane or bike lane, which eliminates double-parking and reduces crash risks.

Myth 2: “Road diets increase congestion”

Reality: For roads carrying fewer than 20,000 vehicles per day (like Trinity Drive), road diets have minimal impact on traffic flow. The center turn lane actually improves traffic flow by removing turning vehicles from through lanes.

Myth 3: “Road diets are bad for business”

Reality: Research shows road diets are good for business. They often increase economic activity by:

Reducing traffic speeds, helping motorists notice local shops

Creating more street parking spaces

Making areas more attractive to pedestrians and cyclists, who tend to spend more money at local businesses than drivers

Providing safer conditions for both drivers and non-drivers

Making it easier for motorists to make turns into and out of businesses

Myth 4: “Road diets slow down emergency responders”

Reality: The available center lane actually makes responding to emergencies easier. Drivers can pull into bicycle lanes to move out of the way, and the center turn lane provides responders with a clear path to pass other vehicles.