Room to grow

How density can make the most out of limited land

Story by Stephanie Nakhleh

Photos by Minesh Bacrania (unless otherwise noted)

Map by Amaya Coblentz

Los Alamos National Laboratory has grown its workforce by more than 50% since 2018, but the town itself hasn’t grown to match. Today, about 10,000 Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) employees commute into Los Alamos daily — many because they can’t find housing, despite having the wages to compete for it.

In the game of housing musical chairs, even LANL’s well-paid workforce struggles to find homes, while many teachers, nurses, police officers, and service workers are priced out entirely. The result is a cascade of consequences: skyrocketing housing costs, staffing shortages at local businesses, dangerous commuting conditions, and a deteriorating downtown.

In 2025, Los Alamos is expected to begin updating its Comprehensive Plan — the County’s official statement of policies, potential strategies, and community values that will govern future development. Most recently revised in 2016, before LANL began its hiring spree, this update creates an opportunity for residents to help shape how the town responds to the challenges of rapid growth. As the community prepares for this planning process, understanding density — what it really means, what it looks like, and how it could benefit Los Alamos — becomes increasingly important.

Julie Campoli, the author of Made for Walking and Visualizing Density, has spent decades helping communities understand how density can solve multiple problems at once. She spoke at the Livability Speaker Series in Santa Fe last September and sat down with Boomtown afterwards to discuss how cities like Los Alamos, with tight housing markets and limited land for expansion, should consider the tool of density.

“Oftentimes, communities think that they are completely built out, and it’s because they have very low-density zoning,” she said. “Re-examining those rules for how big a lot should be or what can occur on a lot frees up an awful lot of development opportunities.”

Change is already here

Change isn’t coming to Los Alamos — it’s already here. The Laboratory’s expansion from 11,743 employees in 2018 to approximately 18,000 today put huge pressure on the housing stock. The question isn’t whether to change, but how to adapt to changes already underway.

The impact of resisting this change is evident in the numbers. According to the newly adopted Affordable Housing Plan, home sales prices increased by 75% between 2018 and 2023, while rent skyrocketed by up to 130%. At the same time, about 67% of Laboratory workers now commute from outside Los Alamos, which has created environmental impacts and safety concerns on the roads.

“The more you’re driving, the more negative environmental impact you’re having,” Campoli explained. “And density makes it possible to cut that number down significantly. In fact, you can’t reduce the amount of vehicle miles traveled unless you live closer together.”

What density really means

When many people hear “density,” they imagine towering apartment blocks or overcrowded neighborhoods. But in Los Alamos, increased density could look quite different. Currently, most residential areas have only 5 to 7 housing units per acre. Housing experts like Campoli recommend modest increases to 10 to 15 units per acre to achieve more affordable housing options while maintaining community character.

“There’s this notion that density is ugly, but it can be very beautiful and appropriate,” Campoli said. “There’s always a beautiful, appropriate solution for your community. It’s incremental; it’s not just one thing. It could mean a backyard cottage, a neighbor on the other side of the wall, a townhouse. Those are all very acceptable, low-key ways to grow denser.”

The key is ensuring new development fits local character through appropriate scale and design, an approach referred to as “gentle density.”

Learning from our past

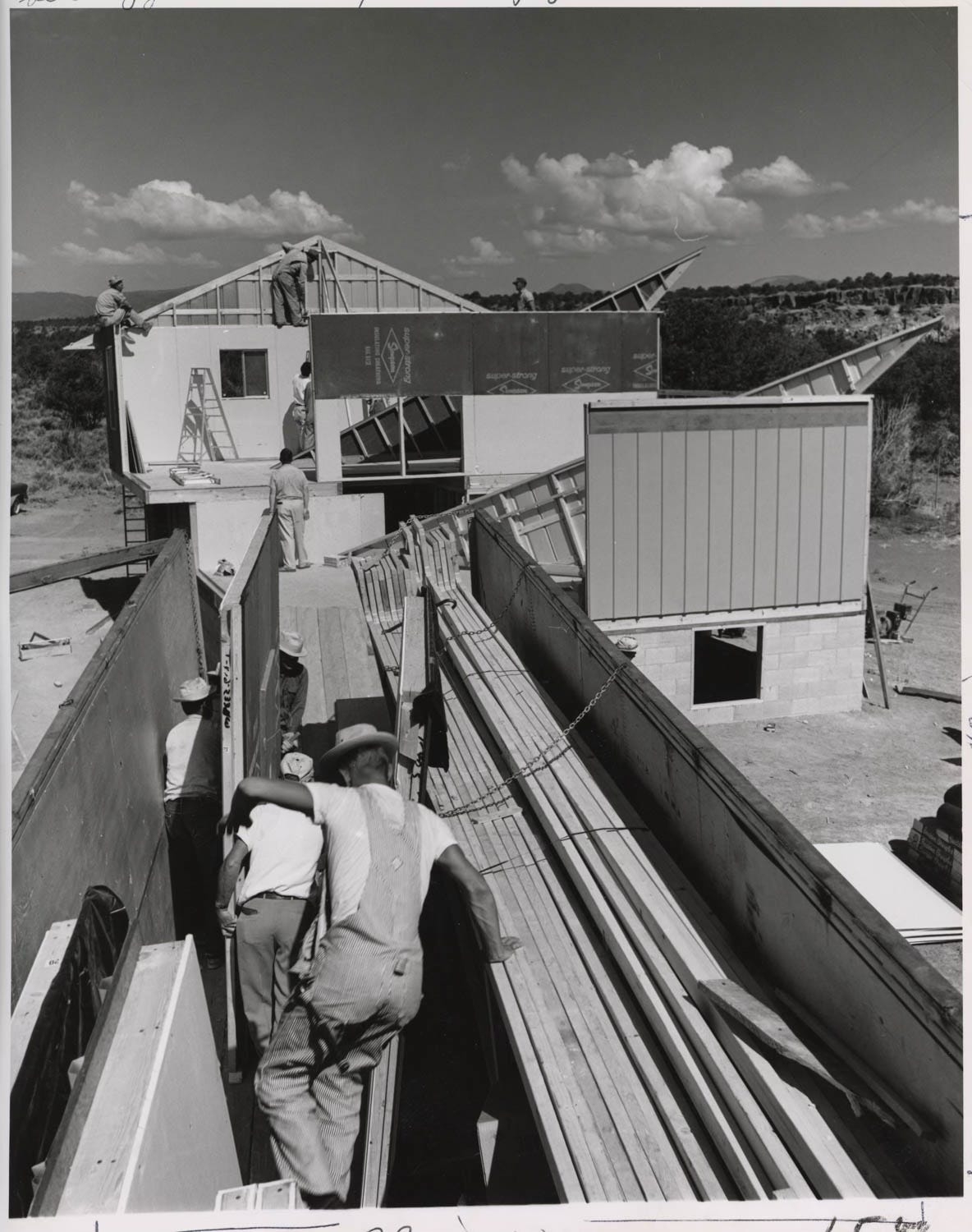

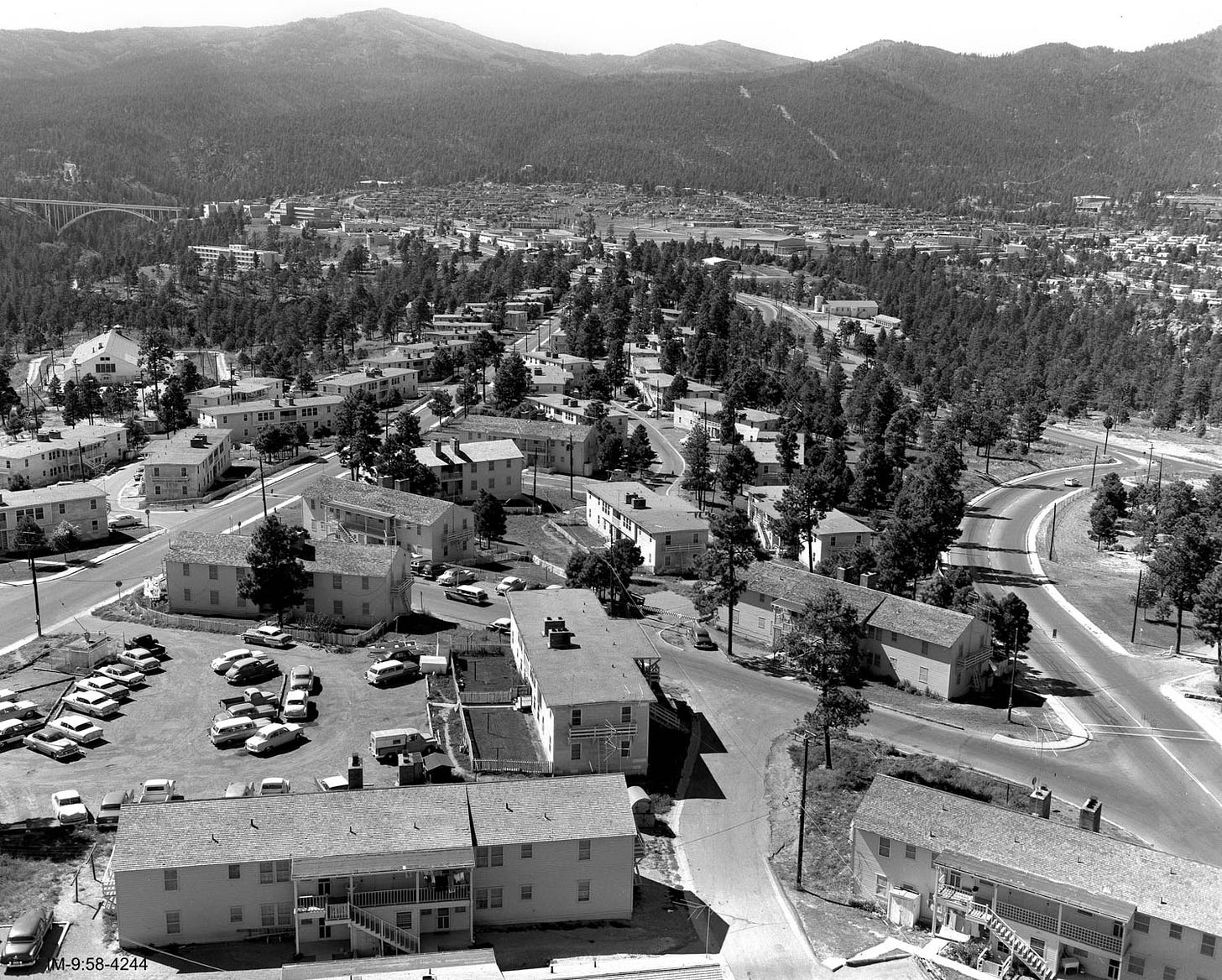

While some residents worry increased density would change Los Alamos’ character, density has been part of the town’s DNA since the beginning. During the Manhattan Project and in the early years that followed, the government responded to intense housing pressure by building not just single-family homes, but duplexes, quads, and small apartment buildings.

Many of these buildings still stand today. According to local historian Craig Martin’s book, Quads, Shoeboxes, and Sunken Living Rooms: A History of Los Alamos Housing, core neighborhoods around Los Alamos include housing many old timers still call by the original names: Group 13 apartments (North Community), Group 14A two-bedroom duplexes (34th and Urban St.), Group 14A apartments (Urban St.), and Group 14B quads (North Community), for example. These buildings, which blend so seamlessly into the residential landscape that many don’t recognize them as “density,” remain among the most affordable housing options in town.

This history offers a lesson as Los Alamos adjusts to another period of rapid Lab growth. Just as the Manhattan Project’s success depended on housing its workforce, today’s Laboratory expansion requires housing solutions beyond the single-family home on a large lot. The town’s historic architecture shows that density can provide needed housing while preserving community character.

Environmental and economic benefits

Density isn’t just about housing — it’s about environmental sustainability and economic vitality. The climate cost of 67% of Laboratory workers commuting from outside Los Alamos is substantial. Denser development patterns could significantly reduce vehicle emissions by allowing more workers to live closer to their jobs, said Campoli.

There are also economic benefits. Despite being one of the wealthiest counties in the nation, Los Alamos’ downtown struggles with vacant commercial spaces. Campoli, who visited Los Alamos while in New Mexico for the Santa Fe talk, saw firsthand the effects of the town’s low-density policies and explained that successful downtowns need people living nearby. “The more people you have living close by, either in upstairs apartments on the second floor or in denser neighborhoods in the back streets around the main street, the more customers you’re going to have for those restaurants and shops,” she said.

Land use reality

Bounded on all sides by federal and tribal lands, Los Alamos faces constraints similar to other high-demand, expensive cities with limited land to sprawl. Some community members pin their hopes on the Department of Energy transferring additional land for housing, but DOE and LANL have repeatedly stated this won’t happen due to contamination and proximity to testing sites. “I don't know what land people were dreaming about,” said LANL director Thom Mason at a 2022 Los Alamos League of Women Voters meeting, when the question of land transfers was asked of him directly. “There’s really not a lot of options, to be honest…Any place you dig in Los Alamos, you’re either going to find unexploded ordnance, historical artifacts [of legacy waste], or you’re going to find cultural artifacts or human remains. So our options for land transfer are actually pretty severely limited.”

Campoli sees the lack of land for sprawl as an opportunity rather than a limitation. “I would see those boundaries as a great asset because it’s easier to do infill development and grow when you’ve got a constraint like that,” she said. “And there’s so much development potential that you already have that can be tapped.”

One example she suggested: approximately 30% of downtown Los Alamos is currently used for parking lots — space that could be reimagined for housing while maintaining necessary parking through more efficient design. At a talk capping his career at Los Alamos County last year, former County Manager Steve Lynne suggested the County could be more creative. “Think outside the box and push a little bit,” he said at the Jan. 18, 2024 Chamber of Commerce breakfast, when Boomtown asked him what the local government could do to promote housing. He pointed out opportunities for mixed-use redevelopment that could include housing, such as properties “with old assets on them” owned by the schools. “We’ve talked about the parking lot in front of the community building,” he said. “That could be a parking structure with housing on top of it.” This vertical growth could take advantage of new building-height allowances without too much reduction in parking. “There’s a lot that can happen,” Lynne said.

Managing tradeoffs

While density offers solutions to housing affordability and environmental challenges, it also brings legitimate concerns that need to be carefully considered and managed. Campoli acknowledged that resistance to density often stems from deeply human reactions to change.

“We are not a species that’s good with change,” she explained in her Livability talk. Research shows people experience more pain from losing something than pleasure from gaining something new. This “loss aversion” can make residents deeply skeptical of development, even when the status quo is creating serious problems.

Concerns about new development aren’t just psychological. While density reduces regional commuter traffic and emissions, it can increase localized activity, construction noise during development, and changes to familiar neighborhood patterns. The key is thoughtful design that creates walkable environments to reduce and calm traffic naturally through building placement and street design.

“By building up a landscape around that street, you’re sending all sorts of visual cues to drivers to slow down,” Campoli said. “Basically, the design of density is really the design of calm traffic.”

Some worry that new neighbors will change community dynamics. But Campoli suggested that what often starts as fear of change can transform into love of vibrancy — once the benefits become evident. “The shockingly new eventually becomes familiar,” she said, “and then it often becomes beloved.”

Traffic worries — and solutions

While residents often worry that increased density will worsen traffic, Campoli said density can actually reduce overall traffic by making public transit viable, but only if enough people live near bus stops to support frequent service.

At the current density levels in Los Alamos, buses can’t run frequently enough to be practical for most residents, Campoli said. “At a density of 3 to 4 units per acre, which is typical suburban...the bus service isn’t going to be very regular. If you want it to come more regularly and not subsidize it so heavily, you need 7 to 8 units per acre.”

According to transit research, a minimum density of about 8 units per acre is needed just to support basic hourly bus service. To run buses every 15 minutes requires 15 units per acre. At 30 units per acre, a tipping point is reached and ridership triples.

Most Los Alamos neighborhoods have only 5 to 7 units per acre — below the minimum threshold for even basic transit service. Increasing density to 10 to 15 units per acre, especially near transit stops, would allow for reliable, frequent bus service that gives people real alternatives to driving. Increasing to 30 units per acre along a key transit corridor like Trinity Dr. could reach a tipping point where ridership would take off.

“You need a critical mass of people in those locations; otherwise, nobody can get to the bus,” she said. This creates what Campoli called a “virtuous cycle”: More residents living near transit stops enables more frequent service, which makes buses practical for more people and reduces car dependency.

Shaping how Los Alamos grows

According to the Affordable Housing Plan, Los Alamos needs between 1,300 and 2,400 new housing units by 2029 to maintain its current status and support economic growth. Meeting this need while preserving community character is possible through thoughtful planning and design, said Campoli.

As Los Alamos prepares to update its Comprehensive Plan, the community has an opportunity to shape how it will grow. By embracing appropriate density increases, Los Alamos could address its housing crisis while becoming more environmentally sustainable and economically vibrant, Campoli said. The alternative is watching housing costs rise further while even more workers commute, local businesses continue to struggle, and the community becomes increasingly exclusive. While Los Alamos may be landlocked, there is room for growth through creative use of the existing residential footprint.

“Most every community I’ve worked with feels like they are not like anywhere else in the world, and that’s fine,” Campoli said. “Everything’s special, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be understood, and it doesn’t mean that it can’t be adapted to the needs of the current time.”