The experience of housing insecurity

Part 4: “People have it pretty good who can live indoors”

Published 3/29/2024

Story by Stephanie Nakhleh

Photographs by Minesh Bacrania

This is the fourth and final in a series on homelessness and housing insecurity in Los Alamos County. The first three articles can be found here.

“The final group in our typology of cities are boomtowns—currently illustrated by the cases of Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco. These cities embody the perfect storm of housing instability and homelessness: high growth, low supply elasticity, high housing costs, and extremely low vacancy rates. It’s in this manner that homelessness can thrive amid affluence.”

-Gregg Colburn, “Homelessness is a Housing Problem”

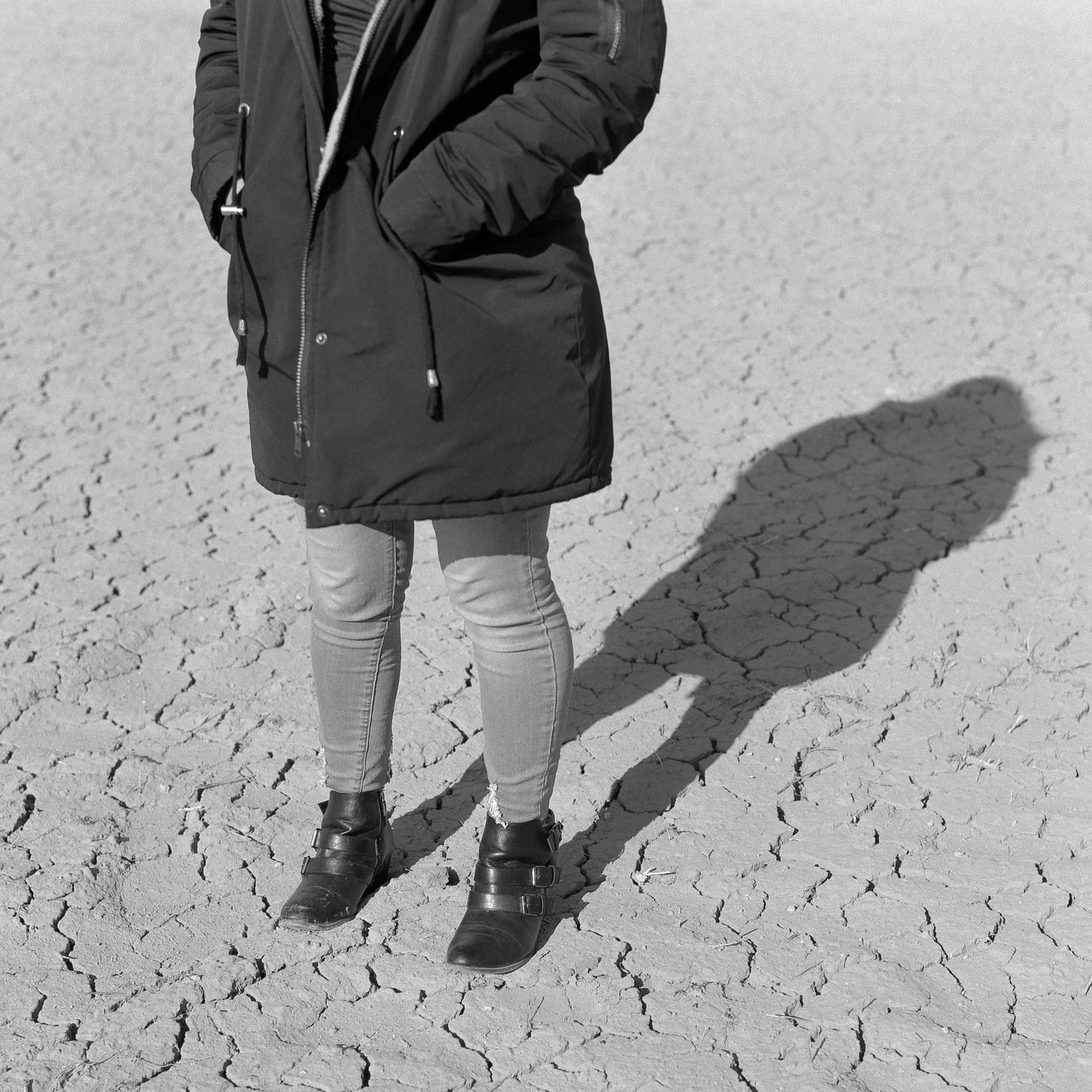

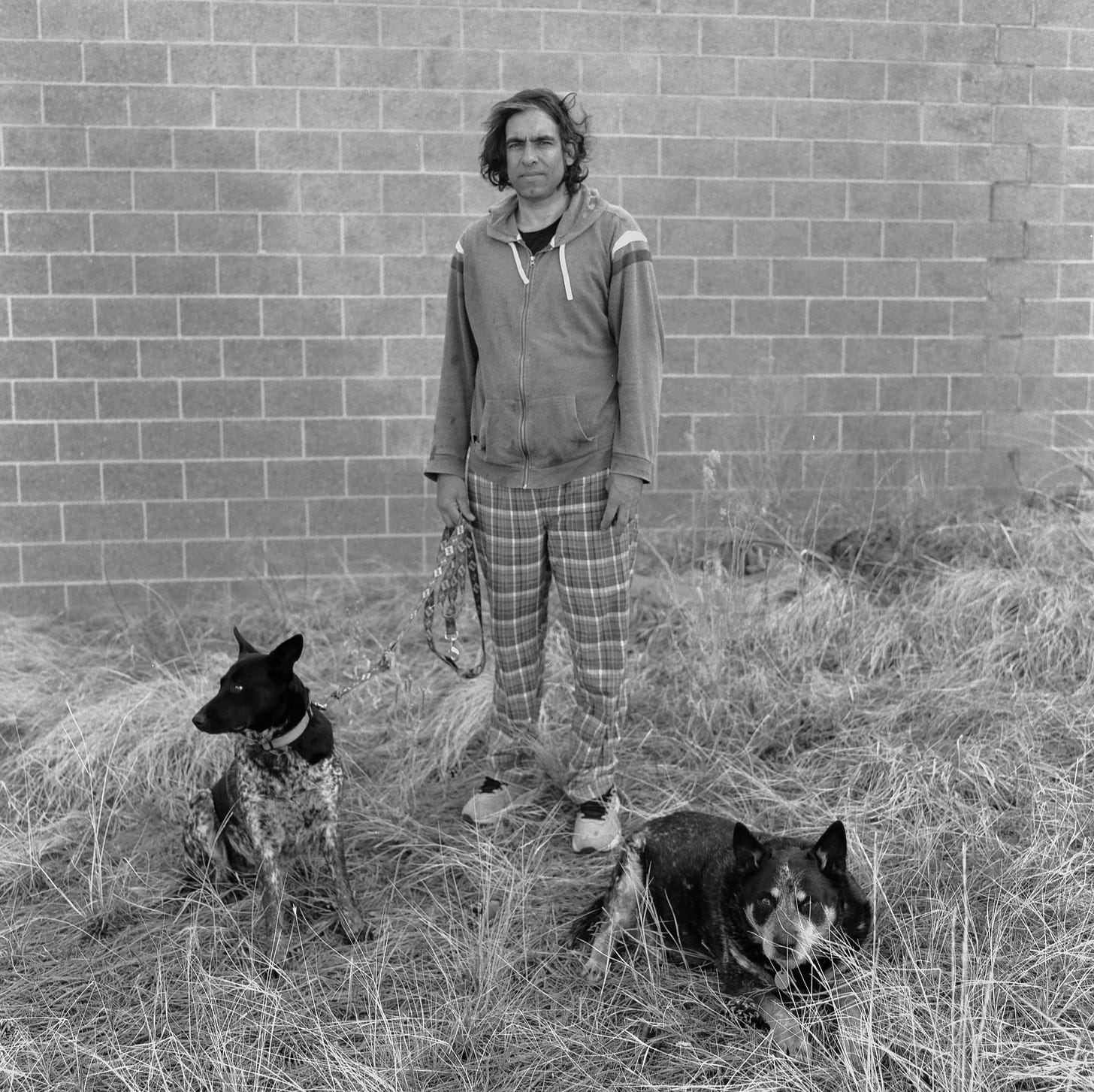

Shibli’s two dogs don’t know they are homeless, but their owner does, and he is trying to get his “family” through a third hard winter in a broken-down car in a Los Alamos parking lot. “People have it pretty good who can live indoors,” he says, as one of his dogs climbs on the picnic table and finishes Shibli’s lunch.

The stereotype of Los Alamos is that everyone is a scientist, everyone is wealthy, and everyone lives in a million-dollar house. That’s not the reality for many in this town. Some residents are holding on to their housing by the skin of their teeth — others, like Shibli, not at all.

“It’s OK, as long as I can stay warm,” he says. “I have a heater. The propane makes a layer of flame over the surface of the ceramic element, so it doesn’t produce as much carbon monoxide. I leave the window open, though.”

When there is more demand for housing than there are housing units available, someone is left out, and it’s usually the most vulnerable people — people like Shibli. We have been speaking to Shibli and others like him who understand housing insecurity from the inside, and today we bring readers a glimpse, a summary, of those conversations. Over time, we’ll be following these stories as their owners are willing to share them.

LeAnn

“It started with a centipede invasion,” says LeAnn Slocum, 42, who lived in the Mountain Vista Apartments for almost nine years. Mountain Vista is an income-restricted complex on North Mesa, built through the United States Department of Agriculture’s “Rural Housing” program in 1983.

LeAnn moved with her young daughter to Mountain Vista in July 2015. “When I first moved in the apartment, it was in good shape from what I could tell. And everything was going fine,” said LeAnn. But about a year later, the centipedes arrived. An exterminator who sprayed the apartment discovered the foundation was cracked, which explained not only how the pests were getting in, but why the apartment was always freezing, says LeAnn.

“After that started the flooding. I think my apartment flooded about six times; I lost count. It was probably about half an inch of standing water downstairs,” she says. One day in 2018, LeAnn returned from work to discover a foot-wide hole had formed in her kitchen ceiling. Water and black mold had poured onto the kitchen floor. She tried to get the maintenance man to take a look, but was told he was out of state, so she cleaned it up herself and waited.

Eventually maintenance took a look. “He said the pipe that runs in between the walls of the two sets of buildings, so the front and back, are just rotted and leaking everywhere, from the bathtub all the way down,” says LeAnn. Unfortunately, he was not allowed to fix it, he told her, because he wasn’t a plumber. He patched the hole in her ceiling instead, but the leak continued and the hole kept opening back up.

Standing water, not surprisingly, soon led to mold. “A couple weeks later, I go to get food to cook dinner and it was soggy in my pantry,” she says. “And I was like what? All my food had mold on it. It happened overnight.”

LeAnn says these problems continued until she moved out in 2023, and that her landlords ignored or did the bare minimum in response to her complaints. “Every time I would tell him, look this can't be good for anybody, they would tell me how it's fine, just mop it up and it's fine.” (Boomtown reached out by phone and by email to Mountain Vista’s management for comment. As of press time, they had not responded.)

Faced with mold, floods, pests, and unresponsive landlords, the obvious solution is to move somewhere better. But moving isn’t an option for many renters in Los Alamos. With more demand for housing than there is supply, renters have nowhere to go. Tenants like LeAnn are trapped in housing — or they lose it entirely.

“I’m in all kinds of Facebook groups [in Los Alamos] and I see people struggling and saying that they're so close to being homeless,” she says. “And I remember that feeling. There were plenty of times I was doing my laundry in the bathtub to save quarters.”

Finally, in 2023, LeAnn was able to get out of Mountain Vista: she now lives in a mobile-home park in Los Alamos, which she says is a big improvement. “I mean there are things about living there, too, but it beats living in a falling-apart apartment,” she says.

Asked how it felt to live in a situation she could not escape, LeAnn’s face changes. She had been focused on the facts, relating her story dispassionately, but with this question comes emotion. “Honestly, I was poor and desperate,” she says. “A part of me was scared, because with all that water, I knew what it was doing — I’m not stupid, right? I knew there had to be mold and I know what it does to people, so I was scared. But I was desperate, and housing in Los Alamos is stupid, and it's outrageous.”

Now that she has a better job, and with it can afford a better living situation, LeAnn is ready to share what she went through — and what she says others are still going through. “That's why now, I’m not afraid to talk, because I hate that people have to go through that. It's not fair. Especially when you're low income. … Just because you don't have the best paying job or you're in a situation where you can't get better housing, we shouldn't have to live like that.”

Boomtown spoke to two other former residents of the complex who confirmed many of the details of LeAnn’s story. Los Alamos County’s Community Development Department and a number of elected officials have also been apprised of the situation. Because of the seriousness of the complaints, Boomtown will be following up on this story.

Jacque

Since the death of her ex-husband almost a year ago, Jacque, 42, has been living with a kind of hidden homelessness called “couch surfing,” moving around from place to place, relying on the generosity of others. She is a native of Los Alamos, having been raised here by her grandparents, whom she refers to as her mom and dad. “My dad was very smart. He’s in the history books,” she says. “He was there before Los Alamos became Los Alamos.” Her dad, according to his 2013 obituary, worked for the Lab for 44 years.

After graduating from Los Alamos High School in 2000, Jacque continued to live at home, working various jobs and taking some classes at the University of New Mexico-Los Alamos. In her mid-twenties she briefly moved to a subsidized apartment in Los Alamos after her mother had a stroke. “She turned mean,” Jacque says. “She basically kind of kicked me out.”

Jacque had lived on her own for only a few years when she had a medical emergency of her own, resulting in an appendectomy. She had to move closer to treatment, she says. Shortly after that, she met the man who would become her husband. When they married, Jacque moved into his family home in Española.

“I didn't understand anything about alcoholism, or anything of addiction, until after we got married,” she says. “I didn't see the red flags. After we got married was when he really showed his true colors. The whole time that we were dating, I didn't understand why he had to have an interlock system, or why his ex-wife always prevented him from seeing the daughter.”

Her husband was accused of molesting his daughter, a crime Jacque says he was eventually cleared of through DNA evidence — but not before he spent some time in jail. “They arrested him and charged him. He had to go through the whole court process,” she says. “Things snowballed, he wouldn't stop drinking, he would spend weeks passed out. The room would reek.”

Eventually things got bad enough that Jacque fled for safety. “I couldn't handle it anymore. He would stop me from using the car, he would stop me from doing anything, I was very captive,” she says.

During the tumult of the final year of his life, Jacque’s husband divorced her. The divorce meant that when he died in May of 2023, she had no claim on the house they shared. “His drinking caught up with him,” she says of his death. “I did end up losing the place because it wasn't our place, it was his place — it was actually owned by my former mother- and father-in-law.”

Jacque has been without reliable housing since, relying on the generosity of others — her pastors, her uncle, her sister, and Anna — for shelter.

It has not always gone smoothly.

Anna

Anna, a physicist, is not facing housing insecurity: Her story is of the other side, the side of someone who is trying to help.

In October 2023, after hearing from a mutual acquaintance that Jacque was facing homelessness, Anna invited the younger woman into her home, giving her a separate apartment with her own bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, and privacy. She let Jacque know this was a temporary arrangement — a soft place to land while Jacque found something more permanent.

Jacque gratefully accepted help from Anna. However, as the weeks rolled on, Anna grew frustrated that she could not get Jacque out of what appeared to be a habit of passivity and into a longer-term plan for self-reliance. Anna tried arranging appointments with doctors, with therapists, with homeless shelters; Jacque promised she’d go, but often missed these appointments. Anna frequently reminded Jacque she would not be able to stay with her forever. “My solution is not permanent,” she tells Jacque again, as we sit together. Anna’s kids would return for Thanksgiving and would need a place to stay.

“I was trying,” says Jacque when I ask her later about Anna’s coaching efforts. “I was doing stuff. I just couldn’t handle, you know, that bombardment. I was like, let me work at my own pace. Because at that time, I was just so overwhelmed.”

After about six weeks, with her kids’ arrival imminent, Anna had to ask Jacque to leave, and Jacque ended up right back where she started: couch-surfing.

It’s easy to lay Jacque’s problems at her own feet, but Anna sees a deeper problem: What Jacque needs, and what many people like her need, is a long-term case manager, Anna believes. “Case management” is described by the Homeless Hub as “a collaborative and planned approach to ensuring that a person who experiences homelessness gets the services and supports that they need to move forward with their lives.” That does not exist in Los Alamos, which lacks the services a bigger city can provide unhoused people, says Anna.

“People in town who are on Medicaid often need to go to Santa Fe,” Anna explains as she, Jacque, and I sit together in October. “But if you don’t have easy access to a car, or transportation, then you’re kind of stuck. [There] needs to be a case manager. It’s not just fixing things [here or there], they might all be related.”

She turns to Jacque: “You don’t have a case manager, right?” Jacque shakes her head: she does not. “I think we could do a better job in town,” Anna says. She believes Jacque, and people like her, need professional help to guide them through the thicket of nonprofit and government social services. But there is nobody in Los Alamos doing that kind of consistent hand-holding, says Anna. “Nobody does case management in town. I talked to all of them.”

I reached out to Los Alamos County’s Social Services Division manager Jessica Strong for comment on what LAC does and does not offer when it comes to case management. Strong replied with the following statement via email:

Per our policy, I cannot comment directly on any current or former client cases. The Los Alamos County Social Services office does provide case coordination services. While it sounds similar, it is fundamentally different from case management, which is more often associated with specific mental health treatment. Case coordination is broader, and involves connecting people to resources and services, hopefully with a warm hand-off. We are strongly guided by a person-first, trauma-informed approach to our work, meaning that we respect each individual’s self-determination and desire to pursue follow-up services.

We are well aware of the challenges facing clients in crisis or with emergency needs, when they bear the burden of following up with various service providers — especially with many providers in Espanola and/or Santa Fe. To address this, we have worked to bring more service providers to Los Alamos — for example, Christine Archuleta, the Housing Specialist for Santa Fe Civic Housing Authority, is now meeting with clients twice a month at the Social Services office. Additionally, we’ll soon begin implementing a closed loop referral software system among providers, that should improve providers’ ability to connect directly with clients.

When Jacque and I catch up on March 13, five months after we first met, she is back to living with her pastors in Española. She has learned that they, too, will need their space back soon. She has to find somewhere else to live. And her car is broken down.

But she has hope. Compared to when we first met, Jacque is bright-eyed and optimistic. She tells me her pastors have set her up with a job as a reflexologist. She is planning to get on the waitlist to move back into low-income apartments on North Mesa. She will get another car. She sees a future. And it is in her hometown, Los Alamos.

Shibli

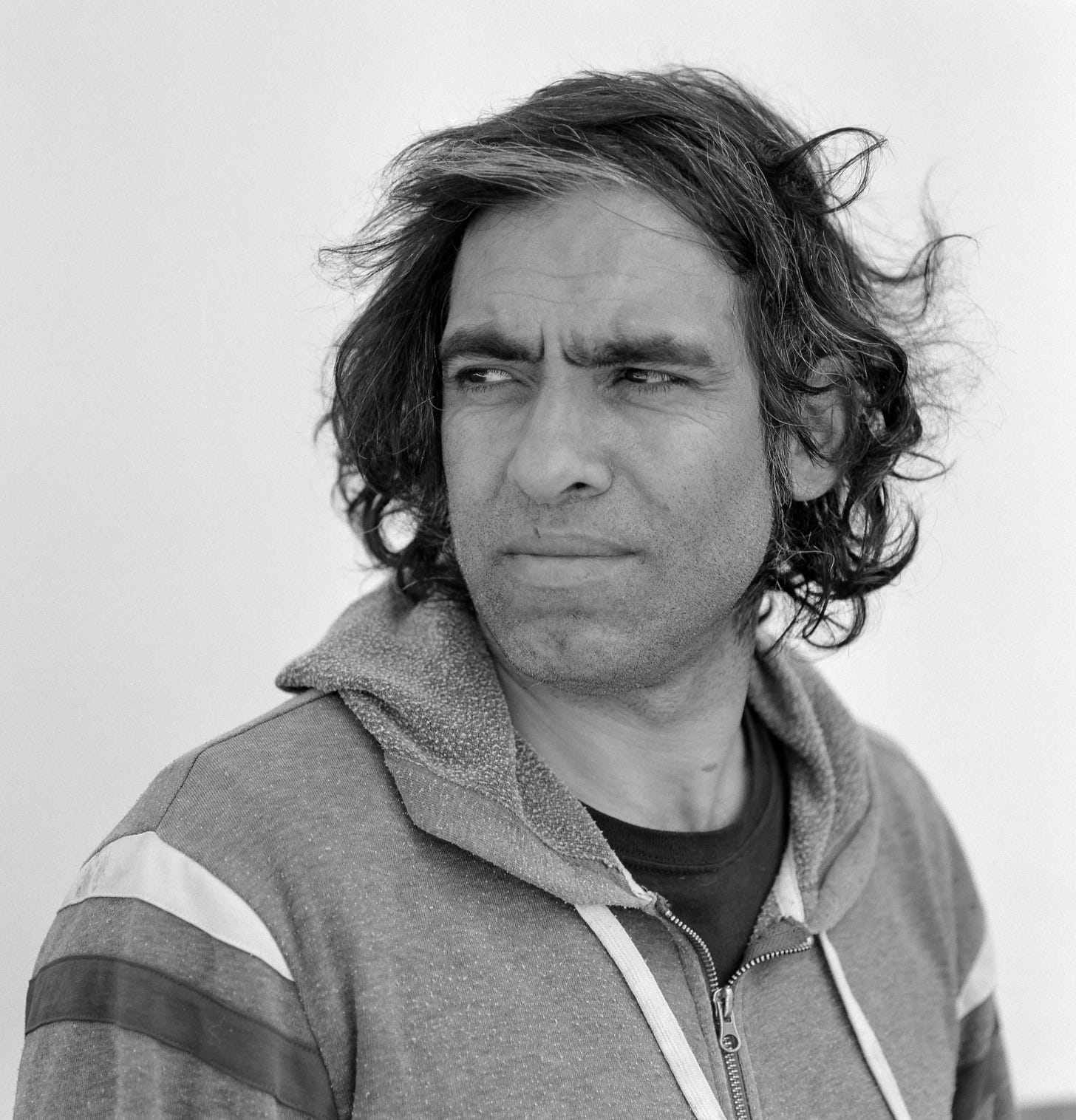

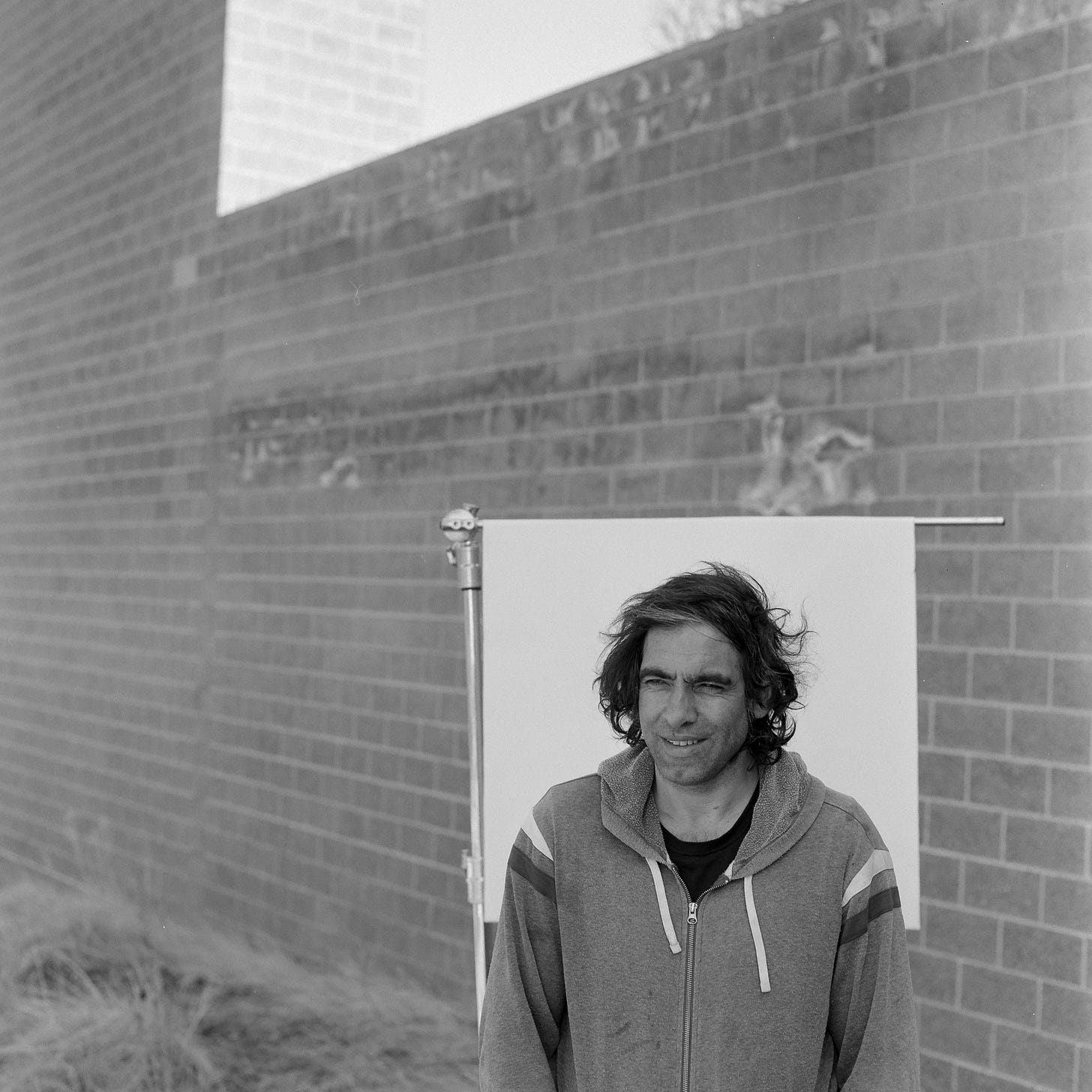

Shibli, 47, lives in a car. He says his two dogs, Froggy and Sakura, are his greatest comfort — but also his greatest challenge. “They are sweet, but they can cause problems,” he says. “Like getting in a fight with another dog. The older one got in a fight when she was in White Rock, she got attacked by three bigger dogs and then she got aggressive.” As if to prove his point, Sakura, the older dog, nips at someone who gets too close to the picnic table where we sit. Eventually, the dog settles and Shibli shares his story with me.

Like Jacque, Shibli’s family has deep Los Alamos roots — in his case, roots that go back to 1946. “My grandfather worked at the Lab, my mom’s dad,” he says. “That was the beginning of things like nuclear energy safety, so the fields were getting diverse.” Shibli’s family moved around a number of times, but he ended up in Los Alamos with his parents in the 1980s and attended Mountain Elementary School. A former instructional assistant who worked with him in the gifted and talented program remembers him. “I taught alongside the GATE teachers,” she wrote in an email. She liked Shibli, she recalls, finding him “quirky but bright, and the kids liked him — at least the kids I liked, liked him.”

As a younger adult, Shibli moved around again. “For a long time I lived in Albuquerque and Los Lunas,” he says. He has family in Los Lunas still, including two teenage sons who are being raised by their mother. She and Shibli have been split for years, but they stay in touch about the kids, he says.

Five years ago he moved from Los Lunas back to Los Alamos. I ask him why. “It’s a little bit safer and more anonymous,” he says. More anonymous, I ask him, even though it’s a small town?

Anonymous, he says, because he’s a local. “It’s from having lived here in the past. You’re just one of those people that went to school in Los Alamos.” People here don’t bother him, he says. They mostly let him be.

When he returned to Los Alamos as an adult, he found housing at first. “I was in the housing program, Section 8, over in the old student housing on 9th Street,” he says, but he was evicted about three years ago. “I didn’t know how clean they wanted you to keep it, so I didn’t worry about it,” he says. “And then they would show up and do an inspection before I could make it perfectly clean. So I couldn’t be in the housing program anymore.”

When we first meet on November 5, 2023, I notice Shibli’s conversational skills are rusty: he spends most days without much human interaction. His expression is wooden, he avoids eye contact. He is polite, welcoming me to the picnic table where he eats his salad, but distant. He goes on a few long philosophical digressions while looking into the middle distance: he reads a lot of books, he listens to a lot of NPR. He ignores my attempts to focus the conversation. But as we spend time together over that warm autumn afternoon, he becomes more relaxed. By the time my colleague joins us to take his portrait, Shibli is joking with us, laughing, and is visibly more at ease.

I ask Shibli why he thinks his life has gone the direction it has. He never answers the question directly, circling around it. “My dad was a chemist,” he says. “It seems interesting to be a scientist but it’s not for everyone; like a lot of people are maladapted, they’re autistic, they’re not very good at having families or socializing or relationships. They have problems in their domestic life but don’t talk about it to a psychologist or anything.”

I ask him how he would describe himself, along those lines.

“Probably kind of like that,” he says. “But I think I have more interest in people, in relationships, than that.”

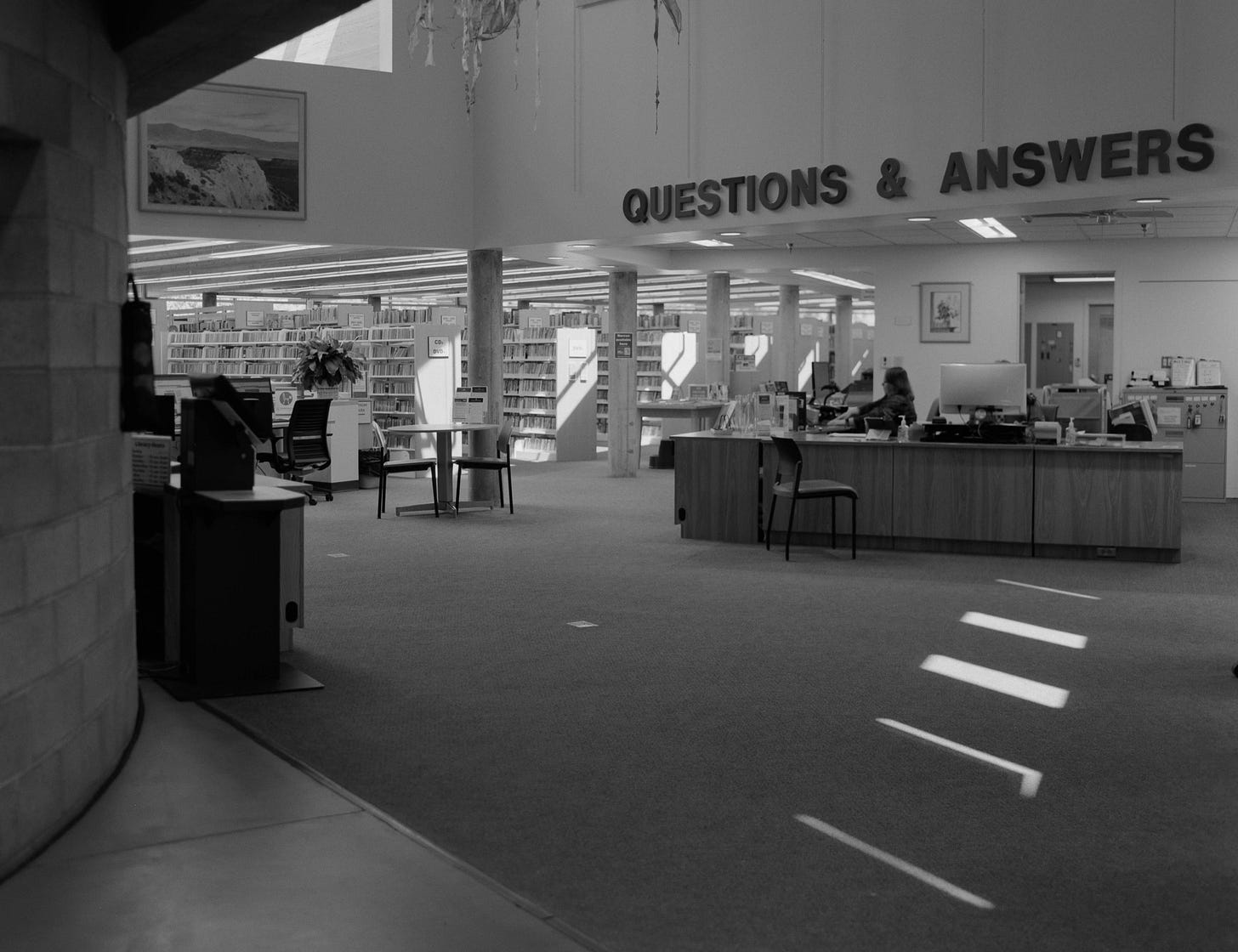

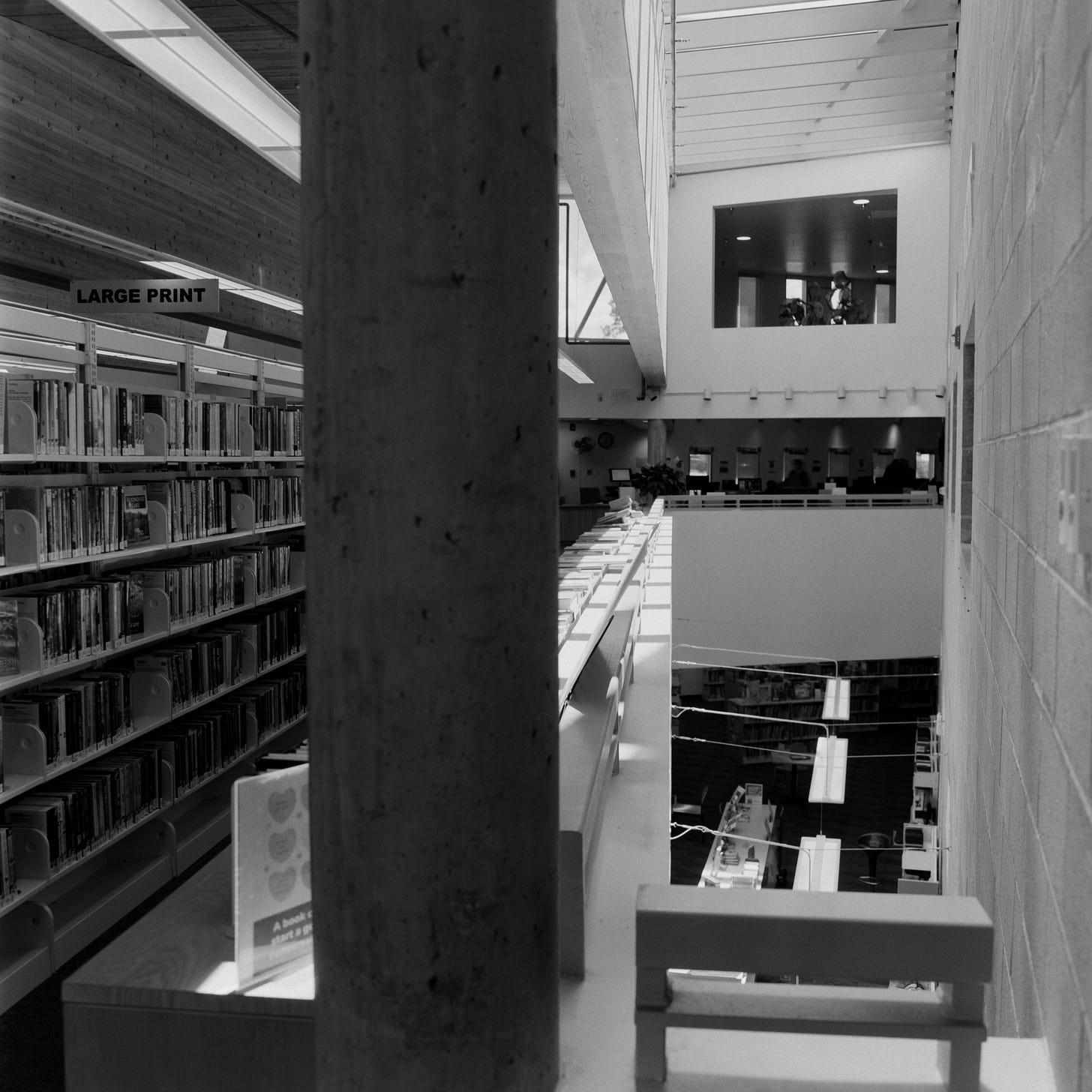

Shibli spends his days mostly at the library, though in the warmer weather this gets difficult because the car is too hot for the dogs. He finds shady places to tuck them away. (Not long after we first spoke, I ran into him and asked him how the dogs were doing: okay, he says, except Sakura had an encounter with a police officer that didn’t go well. “She’s on probation,” he says, mournfully.)

As we sit together near the library in November, Shibli scoops some food for the dogs out of a big bag of kibble. Sakura’s protectiveness aside, the dogs appear fed, clean, happy, and healthy. Froggy in particular is a ball of affection who can’t stand to be left out of the conversation. Sakura side-eyes me as I talk to her person, but Froggy wants to be in my lap.

Back when his car was working, “I was trying to get outdoors more and get the dogs to go outside and have that experience,” Shibli says. “I miss doing that from rock climbing. I used to go fishing with my grandfather, or just spend time outdoors exploring and hiking.” With his car broken down, his range is limited to places he can walk or take the bus. In addition to spending time at the library, he takes martial arts classes, reads books, or exercises at the gym. He has a small income stream from Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and from doing odd jobs for regular clients around town, mostly yard work. He is applying for steadier jobs.

He's not sure what’s wrong with the car. If the car could get fixed, it would be “life changing,” he says. For one thing, he could go visit his kids.

“I just want to go visit my family,” he says. “[We] could go to the skateboard park in Albuquerque. My younger son, I bought him a bicycle, so he’s been doing that a lot.” He says his sons do know he’s unhoused. “They probably worry about me a little bit, but they're not too concerned because they know that I can survive,” he says. He texts them regularly.

Even if his car is fixed, he wouldn’t move to Los Lunas, he says: he’s already tried that. Los Alamos is where he wants to be for now. It feels safer, it feels like home.

Norma

Norma Covington is housed now, but she went through a rough spell in her youth that taught her how precarious housing can be. “I was homeless in college, in Dallas-Fort Worth, couch surfing, living in my car,” she says. That personal brush with homelessness taught her that it can happen to anyone, that losing housing isn’t necessarily a mark of poor decisions or flawed character. “For me, it drove home the idea that homelessness is not a moral situation.”

This lived experience later drove her to work with children, engaging them in activities to support those in need. “We would go door to door in a wealthy neighborhood in El Paso, TX, making go bags. Ziploc bags,” she says. “We’d put in pads, tampons, water, Band-Aids, hand warmers. … Having the kids pack the bags and be involved in that — and sometimes they’d help hand out depending on their age — was instrumental in helping them see homeless people as people.”

Norma is the adult-services librarian at Mesa Public Library. Because of what she went through in college, she understands something of what unhoused patrons who show up at Mesa Public Library are going through.

“Not everyone is like I was when I was homeless, but it’s something that informs my work as a librarian,” she says. “I want to encourage my staff to have that empathy. Working with the homeless is an essential part of being a librarian. Seeing people as people, making the same allowances to that population as you would to any other population — that can really be a good thing.”

She describes her husband, a Christian minister, as a compassionate man whose support was crucial during their early marriage when they again had to navigate periods of housing instability. Reflecting on their shared experience being “lightly housed,” she talks about the challenges faced by individuals without access to stable housing, particularly during the pandemic when basic necessities were difficult to obtain without a fixed address.

“We experienced being unhoused, living with relatives, for a couple of months in El Paso,” she says. “We were lucky enough to have that support or we’d have been homeless with my daughter. During the pandemic, my husband worked in Albuquerque at First UMC (United Methodist Church), and he would tell me the kinds of things he saw there … That was a really tough time for him to see the level of homelessness there in Albuquerque.”

She has seen firsthand how easy it is to lose housing: “In my nonprofit church life, you saw homeless people that came into homelessness through all different means. There’s a misconception that it’s always drugs, or a drinking problem, but I knew just as many who had one bad thing happen: they lost a job, they had a car break down, they had a medical bill.”

That last “one bad thing,” an unexpected medical emergency, was what pushed Norma into the second housing crisis of her life. “Our daughter was in NICU [Neonatal Intensive Care Unit] for a month and we got slammed with medical bills that we could not pay,” she says. “That put us in a precarious situation.”

Affordable housing in Los Alamos is scarce, and becoming scarcer, she says. “Certainly, housing costs are skyrocketing. When I was working minimum-wage jobs, there was no way you could live in most kinds of housing, pay all your bills, and have any money to set aside for medical bills. When those happened, they were extra bad, because you’re already down in a hole. And rental rates are rising here. Plenty of people in Los Alamos work regular jobs and don’t make tons of money. It’s a very tight housing market. It seems to be almost luck if you end up with a place — and then, can you keep it?”

As a librarian, Norma views public libraries as inclusive spaces where individuals from all backgrounds are welcome. “There’s a quote by Linda Stack Nelson, who said something like, ‘libraries are the last place people can simply exist without expectation of spending money.’” (The full quote is part of a piece on libraries that can be read here.)

Libraries often serve as a refuge for unhoused people seeking warmth, resources, and assistance, Norma says. But she doesn’t pry. “When you come to the library, I’m not worried about what you’re coming in for. Whatever free resources you’re there for, we’re there to help. A library is a more welcoming atmosphere than other places.”

When I asked her about solutions, she says, “Solutions as a librarian or as a person? As a librarian I would like to see more available resources. There are resources, but the people who need them can’t always access the information. Especially when we’re talking about the homeless. No access to the internet, they may not have a cell phone they can count on. And they see something that says, ‘just get online and apply?’ It doesn’t make sense.” The library staff is working with the staff of Los Alamos County’s Social Services Division to have that information more readily accessible, she says.

In college, Norma’s transition back into housing was facilitated by a friend, Dustin, who provided financial assistance for a down payment on an apartment. “That’s what I want people to understand: It’s not just becoming homeless; it’s getting out of it. I would not have gotten out by myself, and I was working full time, I was a student full time. It’s expensive to be homeless. I think about Dustin all the time.”

No easy answers

I began this series by writing about the big picture, taking a higher-level look at Los Alamos housing insecurity. But our county’s housing crisis isn’t just about policy, it’s about people — and too often, the people most affected are left out of the story entirely. These are members of our community, who belong here as much as any neighbor. It's important we listen to them.

Writing about the struggles of real people is a huge responsibility, and one I took very seriously. Each of these individuals gave me permission to share their full name, but in some cases I chose to redact the surname to shield them, a little bit, from harsher judgments.

Norma’s experience led her to an understanding she wants to share: People who are securely housed don’t always see the systemic barriers faced by unhoused people, including social stigma, limited access to resources, and the challenge of securing employment and housing without a permanent address. With so many obstacles, staying housed is often more a matter of luck than of skill or hard work.

“We always talk about remembering that we are that lucky and that we did have that break,” she says. “We were able to claw our way out of some of that [housing instability] and now we have respect and empathy for people who are in situations like we were in before.”