The hidden costs of feeding wildlife

Why good intentions can lead to tragic outcomes

Note: this article contains images of deer killed by predators or disease.

Last year, a mountain lion killed a large husky-mix dog in Los Alamos, dragging it from its backyard and caching the carcass near a popular trail by Sioux St. When New Mexico Department of Game and Fish Officer Ariel Perraglio responded, she found the animal aggressively guarding its kill just yards from where children regularly play.

“The mountain lion was sitting and feeding on this dog,” Perraglio told Council at the May 16, 2023 meeting. Several wildlife experts had gathered to plead with Council for help managing the wildlife problems in Los Alamos County. “Right behind that was the trail that kids were using after school. When I was looking in the area, I did come across that mountain lion. I tried to yell at it to get it to leave the area, and it didn't. It was pretty territorial, displaying abnormal behaviors, just aggressive.”

Because of the immediate danger it posed, she had to shoot and kill that mountain lion, Perraglio said.

This incident was just one of several examples the officer recounted of a growing wildlife crisis in the County. In a mere 10-day span prior to that Council meeting, Perraglio had responded to multiple serious wildlife incidents in Los Alamos. Her frustration led her to reach out to County Councilor Randall Ryti, who requested the item be discussed at the May 16 meeting.

Despite its small size, Los Alamos generates three times more wildlife complaints than neighboring communities like Española, Jemez Springs, and Cuba combined. While some residents view increased wildlife presence as a charming aspect of mountain living, wildlife experts warn that abnormal animal behavior – particularly the loss of natural wariness around humans – signals a dangerous shift in the ecosystem.

In November 2023, Council considered an ordinance that would ban wildlife feeding within the County. It was voted down in December, with Council instructing staff to instead conduct an educational campaign on the dangers of feeding wildlife. Data about animal-involved vehicle accidents presented at the Oct. 22, 2024 Council meeting indicated that the problem is not improving.

As the County Council prepares to again discuss potential wildlife feeding regulations at its Dec. 17, 2024 meeting, experts beg residents to understand why feeding wildlife, though well-intentioned, creates cascading problems for both animals and humans.

The urge to connect

“People just want to connect with animals. That comes from a really good place,” said Keila Gutierrez, a wildlife expert with the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance, in an interview with Boomtown. “It comes from recognizing that we’re connected to them, that our ecosystems and societies aren’t really separate. I think that’s ultimately positive, but it can lead to engaging with wild animals in ways that aren’t benefiting them.”

Many Los Alamos residents believe wildlife needs human assistance following the devastating wildfires that scarred the Jemez Mountains. “The drought and past fires have destroyed much of the animals and birds [sic] habitat and food and water sources! … I love the birds and animals in my yard! It should be my privilege to care for them if I choose!” wrote one resident in public comment the County solicited on the issue.

However, research shows a more nuanced relationship between fire and habitat: post-fire vegetation often provides improved forage for deer and other wildlife. According to studies in the Valles Caldera, the burned areas now offer abundant grass and browse that support healthy wildlife populations.

“The vegetation and forage is so good for them outside the city now that we shouldn’t be seeing them within city limits,” explained Dr. Elin Crockett, state wildlife veterinarian for New Mexico Game and Fish, at the same County Council meeting where Officer Perraglio spoke in May 2023. “They should be doing just fine on the landscape on their own, without depending on artificial feeding.”

The wildlife problems in Los Alamos stem mostly from a very particular source, say experts — deliberate feeding, rather than accidental or incidental feeding. “From my experience, correctly placed bird feeders, placed for the purposes of attracting birds, or recreational gardens and fruit trees, grown for human consumption do not appear to be the root cause of incident clusters,” said New Mexico Game and Fish Officer Tyler Carter. “However, the misuse of these same attractant types do.” Carter, who lives in Los Alamos, is the primary officer who manages wildlife-related calls in the County.

The deadly toll of disease

Perhaps the most insidious impact of wildlife feeding is disease transmission. Artificial feeding encourages unnatural congregation — both in number of animals and interaction between species. It creates the perfect conditions for spreading parasites and pathogens.

Dr. Kathleen Ramsay, a Los Alamos native and local wildlife expert who founded the New Mexico Wildlife Center in Española, is well known for her work rehabilitating sick and injured wildlife. In an email interview with Boomtown, she broke down the diseases spread by human interference into two categories. First, those primarily affecting wildlife: Chronic Wasting Disease is an untreatable prion disease that spreads among deer when they congregate unnaturally in groups. CWD has been found in southern New Mexico, though not yet in Los Alamos. Fibropapillomas are tumor-like growths on deer that spread between them when they gather too closely together. Ear mites also spread between deer in close quarters, causing their ears to droop.

Then Dr. Ramsay listed diseases that can spread from wildlife to humans: Bubonic plague can spread to humans through flea bites from infected squirrels and can be fatal if not diagnosed quickly. Tularemia can be transmitted from rabbits to humans and dogs, though it is usually treatable if caught early. Raccoon roundworm (Baylisascaris procyonis) can cause blindness by affecting the central nervous system.

These zoonotic diseases become a greater risk to humans when wildlife are encouraged to congregate in residential areas through feeding. “Los Alamos has many cute little critters that we love to watch. But feeding them and bringing them close to your home is not a good idea,” she wrote.

Public safety at risk

Beyond disease, wildlife feeding creates direct safety risks for residents. In the past year, there were 84 human-wildlife incidents recorded by local authorities, including:

10 reports of wildlife showing aggression toward humans

5 wildlife complaints with an immediate threat to human safety

18 incidents where pets, livestock, or deer were killed by a predator

5 sickly animals removed from town limits

1 unprovoked deer attack on a small child

“I’m very worried about a serious wildlife attack on individuals,” said Carter in an interview with Boomtown. “That’s my big concern. … we’ve gotten dangerously close to something like that happening several times.” He declined to offer details, saying he would describe those incidents at the Dec. 17 County Council meeting.

Perraglio said that across town, deer feeding has attracted mountain lions, which sometimes stow deer they’ve killed in private backyards or near schools and hiking trails. Mountain lions (also known as cougars) cache their kills by covering them with debris and return repeatedly to feed, often defending these caches aggressively.

“So far, the county has been lucky with our cougars, but if they want to kill humans, they can,” warned Ramsay. “When the deer numbers return to normal, so will the cougar numbers.”

Surprisingly, even deer can pose a threat to humans, said Perraglio. A resident provided photo and video evidence to Game and Fish of someone feeding “buckets of corn to deer” daily, drawing crowds of 15-20 deer at a time. The deer had become so habituated to humans that they were “aggressively following her children walking on the sidewalk, presumably looking for food,” Perraglio reported.

Perraglio said New Mexico Game and Fish receives nearly triple the number of wildlife complaint calls from Los Alamos as it does from Abiquiu, Española, Jemez Springs, Ponderosa and Cuba combined. These numbers didn’t include complaints about coyotes and raccoons, focusing solely on mountain lions, bears, and deer. Wild animals in Los Alamos are not behaving the way wild animals should behave — and that is primarily because of human interference.

“This is abnormal behavior,” said Perraglio. “A mountain lion killing a deer in a canyon outside of town? Totally normal. But taking something from somebody’s backyard where there’s people around, or something from the stables where there’s a lot of people around? That’s abnormal. These mountain lions, we can’t allow them to continue to be around people.”

“We’re killing deer with kindness”

Perhaps counterintuitively, feeding wildlife often leads to malnutrition. Deer, for instance, have complex digestive systems that require specific seasonal diets. When well-meaning residents offer corn or other inappropriate foods, they can cause the animals to have fatal digestive issues.

And “inappropriate food” is precisely what many Los Alamos residents are feeding wildlife. Perraglio received reports “of an individual who’s feeding hot dogs, apples, chips, and corn to deer on the softball fields next to or near the stables on North Mesa,” she told Council. (Boomtown has also heard complaints from the Little League community about this individual, a habitual feeder.)

Experts say that hot dogs, potato chips, and corn are not appropriate foods for wildlife. A diabetes-like metabolic condition can develop in deer when they eat too many carbohydrates from human food like corn. Rickets can develop in deer when they rely on artificial food lacking proper nutrients.

If you give an animal “a choice between a Snickers bar and a bucket of good quality grass to eat, they’re going to eat the Snickers bar,” explained Dr. Ramsay. “We’re killing deer with kindness. Their complex digestive systems can’t handle sudden changes to high-carbohydrate foods like corn.”

“They were here first”

A common refrain on social media when residents raise concerns about wildlife behavior is “Wild animals were here first, stop complaining, it’s just part of nature.” While it’s technically true that wildlife preceded human settlement, experts say this perspective misses an important point.

“That mindset comes from acknowledging that yeah, they were here first. But what are we doing? We’re going the other way with it,” said Gutierrez. “We’re not just passively coexisting — we’re actively inviting and encouraging them into developed areas. That’s very different from saying ‘They’re supposed to be here anyway.’”

The current situation — with deer, coyotes, bears, and mountain lions regularly wandering residential streets — isn’t natural behavior, experts say. Wild animals are safest in their wild habitat, not in town. “The best thing you can do when you see a bear is leave it alone,” said Gutierrez. Enjoying our wild neighbors is part of mountain life, “But that doesn’t mean we should encourage wildlife to actively seek out our yards by leaving food for them,” she said.

Wildlife and cars

Feeding wild animals brings them into residential areas, creating dangerous conditions on Los Alamos roads. According to Police Chief Dino Sgambellone, the county saw 62 animal-related crashes in 2023 and 48 through Sept. 2024. Most involved deer, though some crashes involved elk, bear, coyotes, and even mountain lions.

The situation mirrors what Ruidoso faced before passing their wildlife feeding ban in 2019. In 2016, Ruidoso officials reported “hundreds” of elk and deer killed in vehicle collisions, with residents blaming tourist feeding for habituating wildlife to populated areas. “Deer will stand in the road and they’ll stand there forever and they’re just so used to people,” a Ruidoso shop owner told KRQE at the time.

This problem is obviously bad for the wildlife that gets crushed by cars, but it’s also dangerous for humans. An adult male elk can weigh a thousand pounds, and antlers can spear people. Another danger comes from swerving around an animal that suddenly appears in the roadway, which can cause drivers to lose control and crash.

“We’ve already done a great job with bear awareness,” one Los Alamos resident said at an August 2023 wildlife education session at PEEC. “But we need to do more about other wildlife incidents before someone gets seriously hurt.”

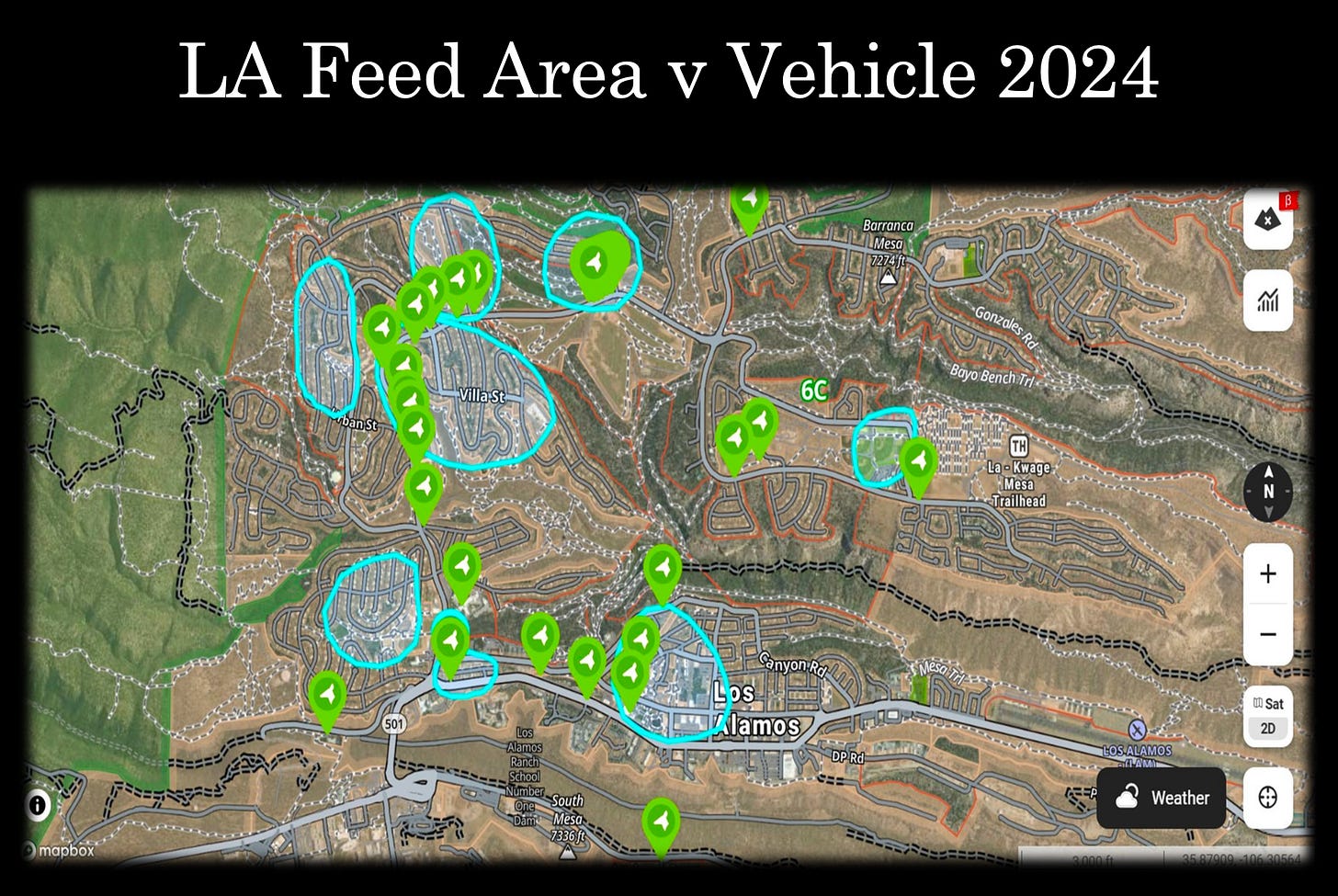

At the Oct. 22, 2024 County Council meeting, Chief Sgambellone’s presentation on road safety included a police department map showing animal-vehicle collisions concentrated along Diamond Drive, though crashes occur throughout the County. A presentation from New Mexico Department of Game and Fish included with materials for the Dec. 17 meeting confirmed that data and added a connection between known “feed areas” and the collisions.

Chief Sgambellone said that research shows even small reductions in speed can significantly decrease crash severity. However, a car hitting an animal at 35 MPH, the most common speed limit in town, will likely still kill or maim that animal. However, speeding cars are not really the issue; the fundamental problem remains the artificially large wildlife populations drawn to residential areas by feeding. “You heard from Game and Fish about the potential to reduce things like this with some sort of feeding [ordinance], not inviting the animals into the populated areas,” said Sgambellone.

How to help wildlife

For residents who genuinely want to help local wildlife, experts recommend focusing on habitat restoration and protection rather than direct feeding. “The best way to protect these animals, especially all these large, charismatic mammals, is to really encourage them to stay in their protected and remote wilderness,” said Gutierrez. Dr. Ramsay shared a similar view: “Nature has taken care of itself for centuries. Why are we trying to change it?”

Practical steps include:

Supporting local habitat restoration projects

Maintaining appropriate distance from wildlife

Supporting science-based conservation efforts

Avoiding feeding wild animals

While the impulse to feed wildlife comes from a place of compassion, the science is clear: the best thing humans can do for wildlife is stop interfering with it.

Los Alamos County Council will revisit potential wildlife feeding regulations on Dec. 17. At the same meeting, Council will consider adopting a comprehensive health plan and receive an update on the plan for the East Downtown Los Alamos MRA.

Residents interested in contributing to these discussions can attend the Dec. 17 County Council meeting at 6 p.m. in person at the Municipal Building (1000 Central Ave.) or via Zoom, or provide e-comment before 11:45am on the day of the meeting.

Great article. Thanks.

This is a great report- lots of good visuals, too.