Wildfire protection as community effort: ‘It takes all of us’

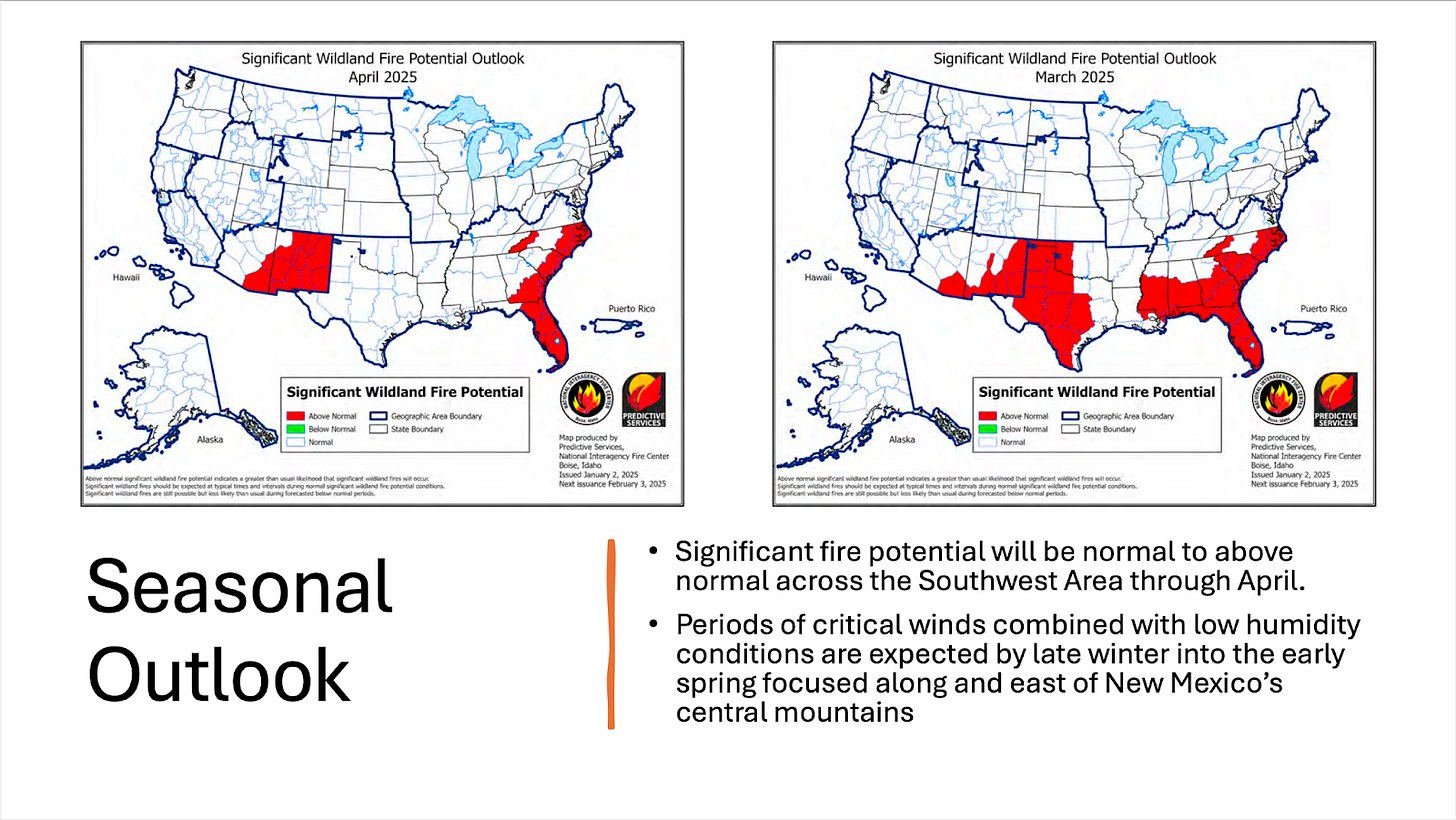

With wildfire season approaching and a dry winter leaving the region vulnerable, Los Alamos officials painted a grim picture at Wednesday’s Wildland Fire Preparedness meeting. Los Alamos Fire Department’s Wildland Division Chief Kelly Sterna said nearly all of New Mexico is expected to face above-normal fire danger by April, with dry conditions, high winds, and an early start to fire season creating serious concerns. Hosted by the Local Emergency Planning Committee, the meeting (available here) aimed to prepare residents and businesses for the months ahead by outlining wildfire risks and strategies for reducing fire danger.

Sterna said community-wide preparation is key to preventing fire spread, particularly as firefighting resources could be stretched thin. With the southeastern U.S. also facing an extreme fire threat this year, national air support and ground crews may be in high demand, limiting the assistance available to New Mexico. “There's only a dedicated certain amount of air resources that the whole country shares,” Sterna said, meaning the community may be unable to rely on air support.

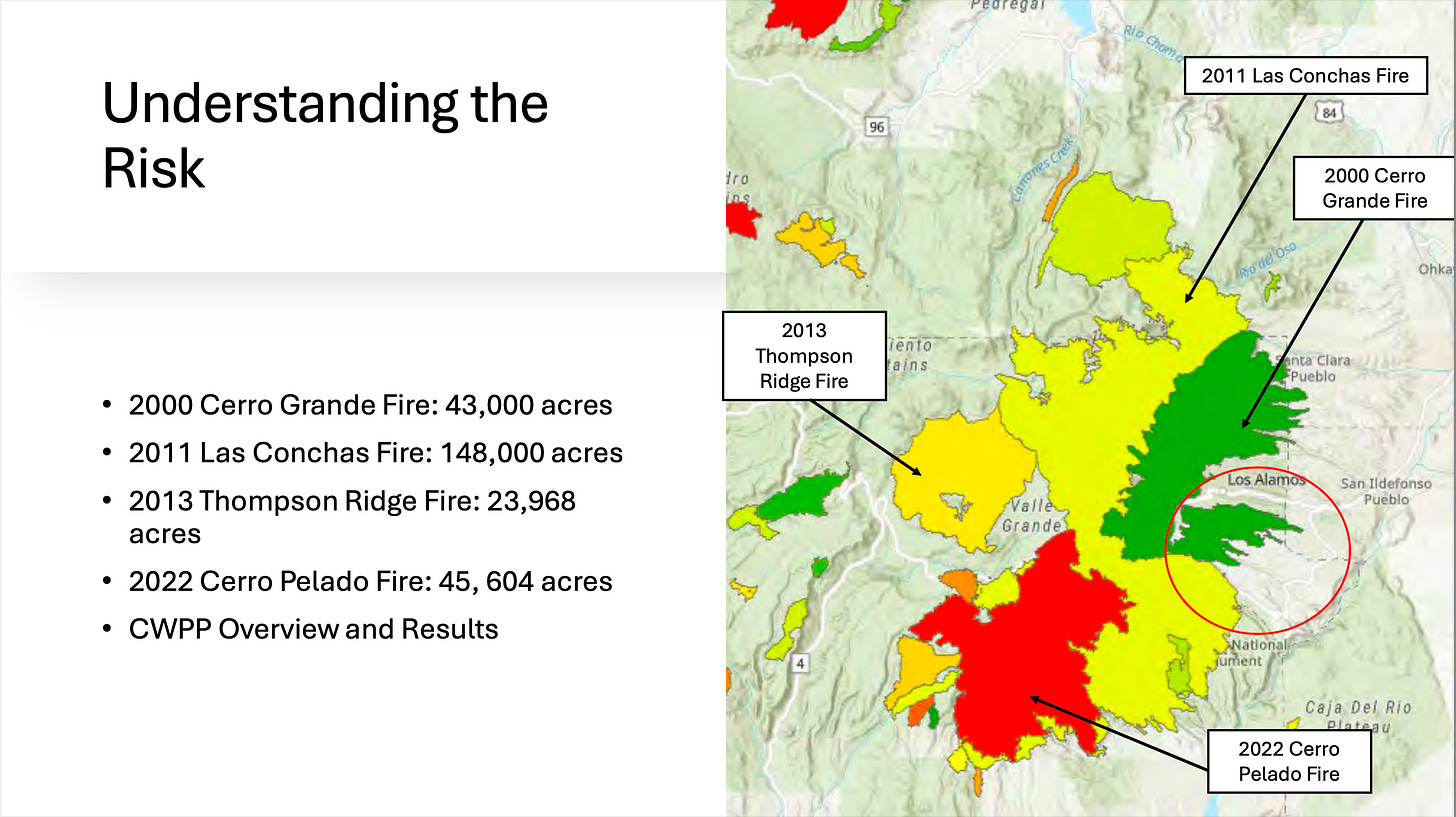

During the virtual meeting, residents learned that current drought conditions mirror those from 2018 — a notoriously dry year. This was unwelcome news for a community that has witnessed town-wide evacuations three times in its history: first during the Water Canyon fire in 1954, then the devastating Cerro Grande fire in 2000, and again during the Las Conchas fire in 2011.

A vulnerable community

Los Alamos County’s topography, with its finger mesas and proximity to the Valles Caldera, creates unique wildfire challenges, said Sterna. Seasonal forecasts show above-normal fire potential starting as early as March and extending through April, when almost the entire state is predicted to face elevated risk.

During the virtual meeting, community member Jeff Fronzak wondered if winds could favor the community in certain circumstances: “What is your level of concern with the canyons that go east from Los Alamos?” Fronzak asked. “Given prevailing westerly winds, the risk seems lower of a fire moving west.”

Sterna explained that while southwest winds are common, summer brings dangerous “back door cold fronts” that can reverse wind direction completely. “When we get dry lightning pushing back into the town site with winds from the north-northeast, that’s a bad scenario,” he said.

The northern sections of town have particularly high fuel loads. “One thing that we can all agree on is there's a lot of trees over in the northern community,” Sterna said. These neighborhoods escaped the Cerro Grande and Las Conchas fires, leaving their thick tree stands intact: “The northernmost part of Los Alamos — North Mesa and Barranca Mesa — have the highest Ponderosa Pine density in the county.”

The FEMA-funded Wildfire Mitigation and Public Education Project has reduced some fuel in these areas, Sterna said, and LAFD will conduct additional fuel mitigation projects on county-owned property in the coming months — including on North and Barranca mesas.

The collective-action challenge

Wildfire preparedness can’t fall solely on emergency responders, said Sterna: “There’s not a fire department on this planet that is going to fare very well when they get multiple homes on fire and a wildland fire.”

When a wildfire threatens a town, firefighters must conduct rapid triage to assess which homes can realistically be saved. This process looks at defensible space, accessibility, and risk to firefighter safety.

“It’s not what people want to hear,” said Sterna, but during extreme conditions, firefighters are forced to make strategic decisions about which neighborhoods to defend. “Once the wind starts driving that fire, that really puts the firefighting response to a very tricky, delicate situation because we can’t put our folks safely in the neighborhoods when we’re seeing 50, 60, mile an hour winds and we have multiple homes igniting. It really comes down to a holding operation in which we look at what neighborhood is going to give us the best chance to stop the forward progression of that fire.”

“There’s not a fire department on this planet that is going to fare very well when they get multiple homes on fire and a wildland fire”

In other words, neighborhoods that collectively invest in fire mitigation are more likely to be defended by firefighters because they provide safer working conditions for fire crews and a better chance of success. The size of a small-town fire department makes this community responsibility even more critical: “We have 40 people on duty per day here in Los Alamos. Los Angeles and Cal Fire have upwards of 1,500 to 2,000 people on duty a day,” Sterna said.

Even one unmitigated property can affect the whole neighborhood. “Unfortunately, the only well-mitigated house is surrounded by its worst-mitigated neighbor," Sterna said. “That’s going to take more time for us to spend on that one really bad home that might take out the neighborhood.”

Ready, Set, Go: A framework for action

The “Ready, Set, Go” concept is a structured approach to wildfire preparedness, leading up to evacuation. Los Alamos County remains in the “Ready” phase (as of this writing), a status that focuses on year-round home hardening and creating defensible space.

Sterna said residents should focus their “defensible space” efforts in the immediate zone (0-5 feet) from structures. Homeowners should remove combustible materials, maintain healthy vegetation, and address vulnerabilities like wooden decks and siding, which can make the difference between a home that survives and one that ignites.

“The number one thing I tell folks is to take before and after pictures of any work that you do,” Sterna said, particularly as there has been concern about insurance companies using satellite imagery to evaluate properties. “Save them to a file on your computer. Because then, if you speak with your insurance folks, and they say, ‘We can’t justify covering you,’ …you actually have evidence that you’ve done the work.”

To date, LAFD has conducted over 500 home assessments, identifying common issues like accumulated pine needles in gutters, low-hanging branches, and deteriorating wooden structures. Residents can request these free, confidential assessments by emailing Sterna directly.

Communication: The lifeline during crisis

During the meeting, Los Alamos County’s Emergency Manager Beverley Simpson addressed questions from residents about communication systems during power outages or overwhelmed cell networks: “Los Alamos OEM has a mobile connectivity trailer that will be used in an emergency. We will also request assistance from both T-Mobile and Verizon to bring in cellular towers and Cell on Wheel platforms to assist with communication.”

The county maintains multiple redundant systems, Simpson said, including a conventional radio system with backup generators, AM 1610 for emergency broadcasts, and partnerships with ham radio operators who can relay messages when other systems fail.

Officials at the meeting leaned on the importance of registering for the CodeRed alert system, which can target notifications to specific geographic areas. Residents can register their contact information by visiting this website, or they can install the CodeRED app by following this link.

Special considerations: livestock and rural properties

For residents with livestock, particularly those in areas like Pajarito Acres or the County stables on North Mesa, advance planning is essential. The California Department of Food and Agriculture resources shared during the meeting outlined practical steps: identifying evacuation destinations, establishing transportation plans, ensuring animals have permanent identification, and maintaining medical records and vaccinations.

“Determine the best place for animal confinement in case of a disaster,” the guidance suggests. “Find alternate water sources in case power is lost and pumps are not working or have a hand pump installed. You should have a minimum of three days of feed and water on hand.”

The path to becoming a Firewise community

Some residents asked about becoming a certified Firewise community, an approach that could address both safety concerns and insurance challenges. The program provides a framework for neighborhoods to reduce wildfire risk through organized mitigation efforts collectively.

“Right now, there’s not a lot of momentum for Firewise in Los Alamos County, unfortunately,” said Sterna. While LAFD supports the concept, “The fire department cannot drive everything, and if homeowners want to get involved with this, we’ll help as much as we can. But it’s important to recognize that the fire department is not going to be driving the bus on all these programs.”

For neighborhoods interested in pursuing Firewise certification, the process involves organizing a community board or committee, creating a wildfire risk assessment, developing a three-year action plan, and implementing mitigation activities representing at least one volunteer hour per dwelling unit annually.

“That’s what’s going to save us”

As Wednesday’s meeting concluded, Lance Fresquez from LAC Emergency Management reminded participants that wildfire preparedness requires collective action: “It takes all of us to be prepared for wildland fire … making sure that as a community, we're all doing our part to protect our structures because ultimately, that's going to protect the whole community.”

Sterna’s final message reinforced the importance of individual and community responsibility in the face of natural forces that can quickly overwhelm formal response systems: “I definitely want to re-stress the importance of homeowners looking after their own property, taking those measures seasonally to maintain their property, because that’s what’s going to save us from a large-scale type Palisades fire event versus the response of the fire department.”

Thank you for putting this together!

You're so welcome!